Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

“You don’t build [the world’s tallest] skyscraper to house people, or to give tourists a view, or even, necessarily, to make a profit. You do it to make sure the world knows who you are.”

-Paul Goldberger, American architecture critic, born 1950.

The Two Cherubs

For nearly all of human history, the space above our heads represented the unknown. Our ancestors would look up in awe, longing to satiate the innate need within us for Verticality. The two little cherubs pictured above encapsulate this innate need to escape the Earth’s surface, and their resulting fame apart from the painting they inhabit serves to illustrate this.

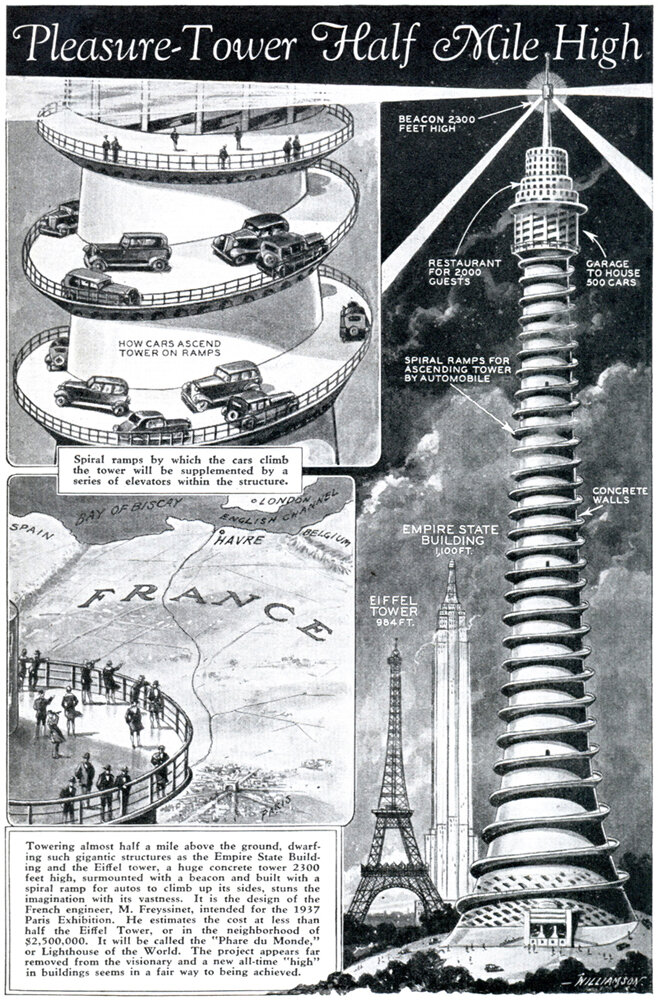

The Phare du Monde Pleasure Tower

Pictured above is a tower proposal from 1933 for the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris. It features an external spiral ramp leading to a parking garage 1640 feet (500 meters) from ground level.[2] Once at the top, visitors would find a restaurant, hotel and observation deck, and the spire contained a lighthouse beacon and a meteorological cabin. The view? Sublime. The design? Utterly ridiculous, unless taken as a satirical statement on civilization’s reliance on the automobile.

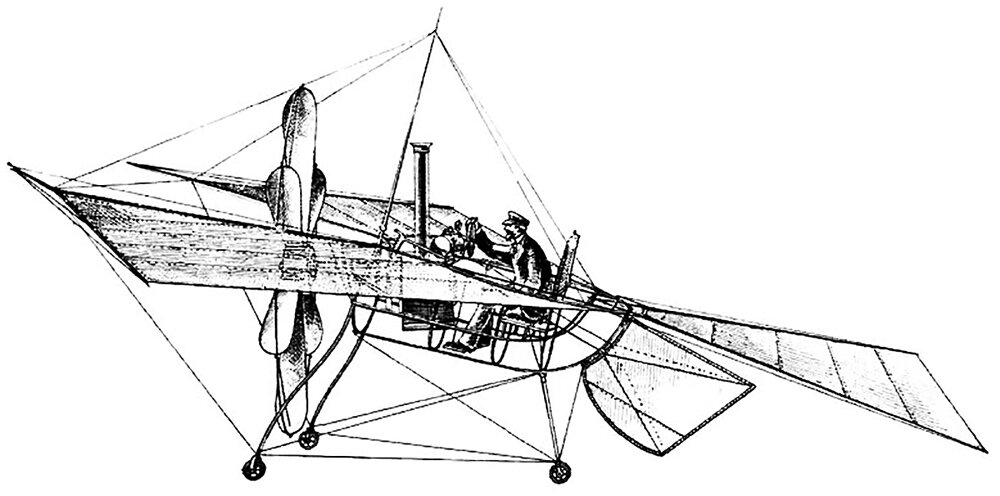

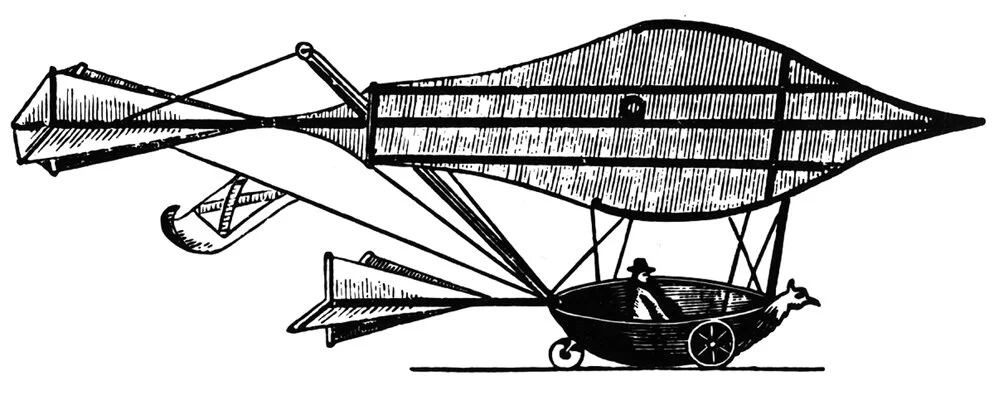

Félix du Temple’s Monoplane

Pictured above is an illustration of Félix du Temple’s design for a monoplane, which he and his brother Luis built and tested in 1874. One such test saw the machine take off from a ski-jump and glide for a bit before safely landing back on the ground. This flight, though short, gave the craft a claim to the first successful powered flight in history.

"[The skyscraper] must be tall, every inch of it tall. The force and power of altitude must be in it, the glory and pride of exaltation must be in it. It must be every inch a proud and soaring thing"

-Louis Sullivan, American architect, 1856-1924

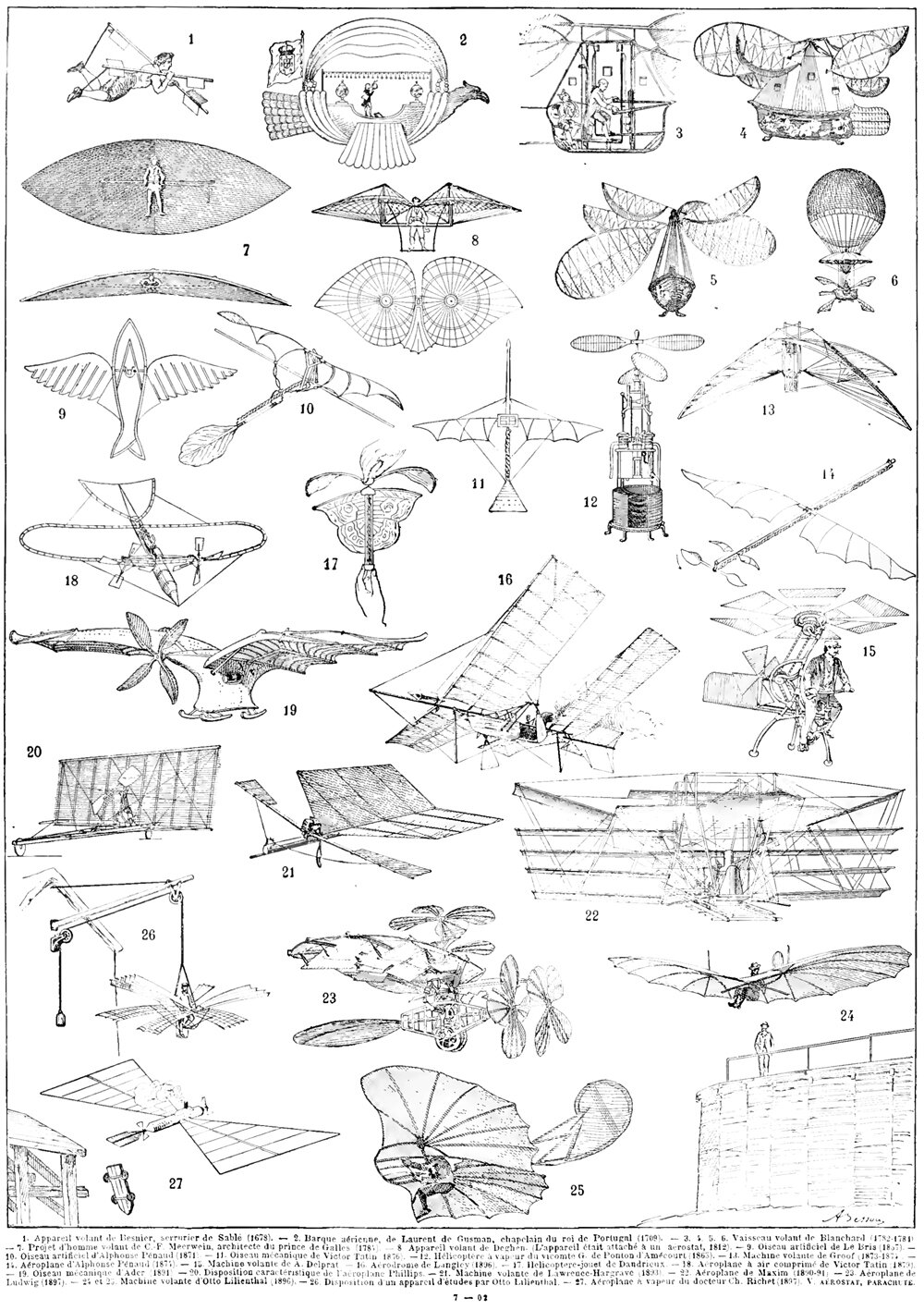

Flying Machines

Throughout history, humans have been fascinated with flight, and some of our more industrious brothers and sisters have dedicated their lives to achieving it. This has led to a rich lineage of ideas for flying machines, and the illustration pictured here shows some famous examples throughout this lineage.

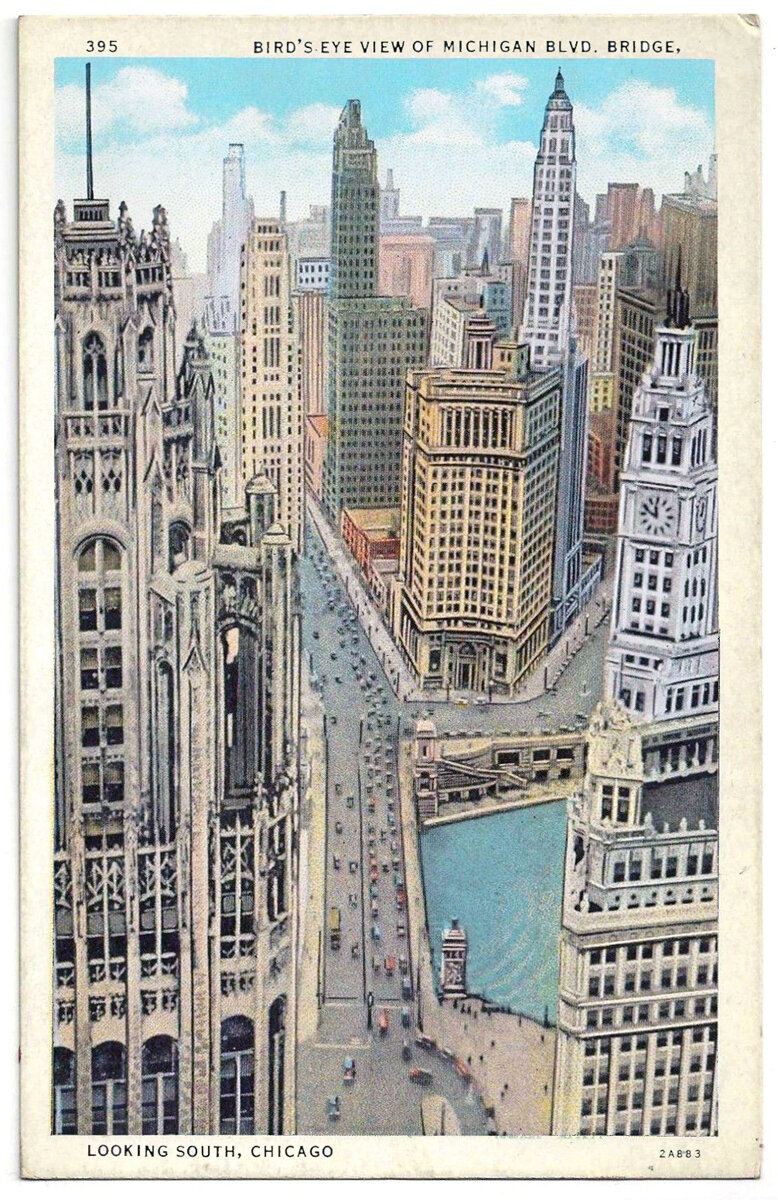

The Urban Canyon

It’s difficult to reconcile the inhuman scale of the skyscraper with the human experience at street level. In most Western cities of today, the experience of walking down the street is largely soul-less, with a relentless street wall rising up on both sides and massive towers rising above that, usually set back from the street wall a bit.

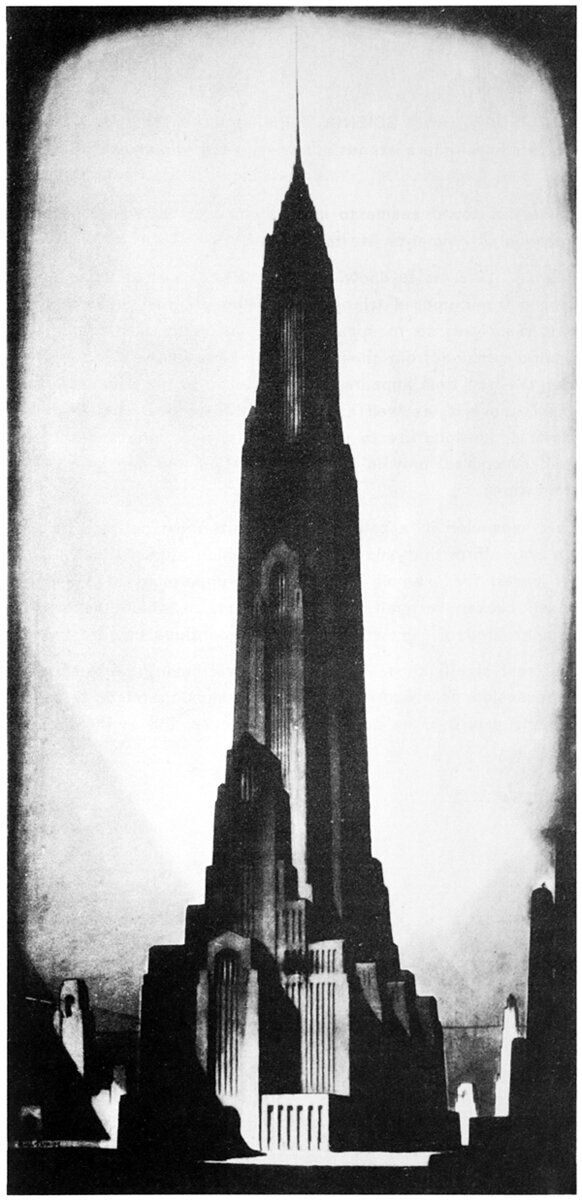

Hugh Ferriss and Religion on the Skyline

Hugh Ferriss was an architect and illustrator, best known for his charcoal renderings of skyscrapers in the first half of the 20th century. Pictured here is an illustration from his 1929 work The Metropolis of Tomorrow, titled Religion. This image and the underlying thought behind it’s creation ties into a larger trend around this time that saw religious structures attempt to re-take the skyline from commerce.

“The problem of the tall office building is one of the most stupendous...opportunities that the Lord of Nature in His beneficence has ever offered to the proud spirit of man.”

-Louis Sullivan, American architect, 1856-1924

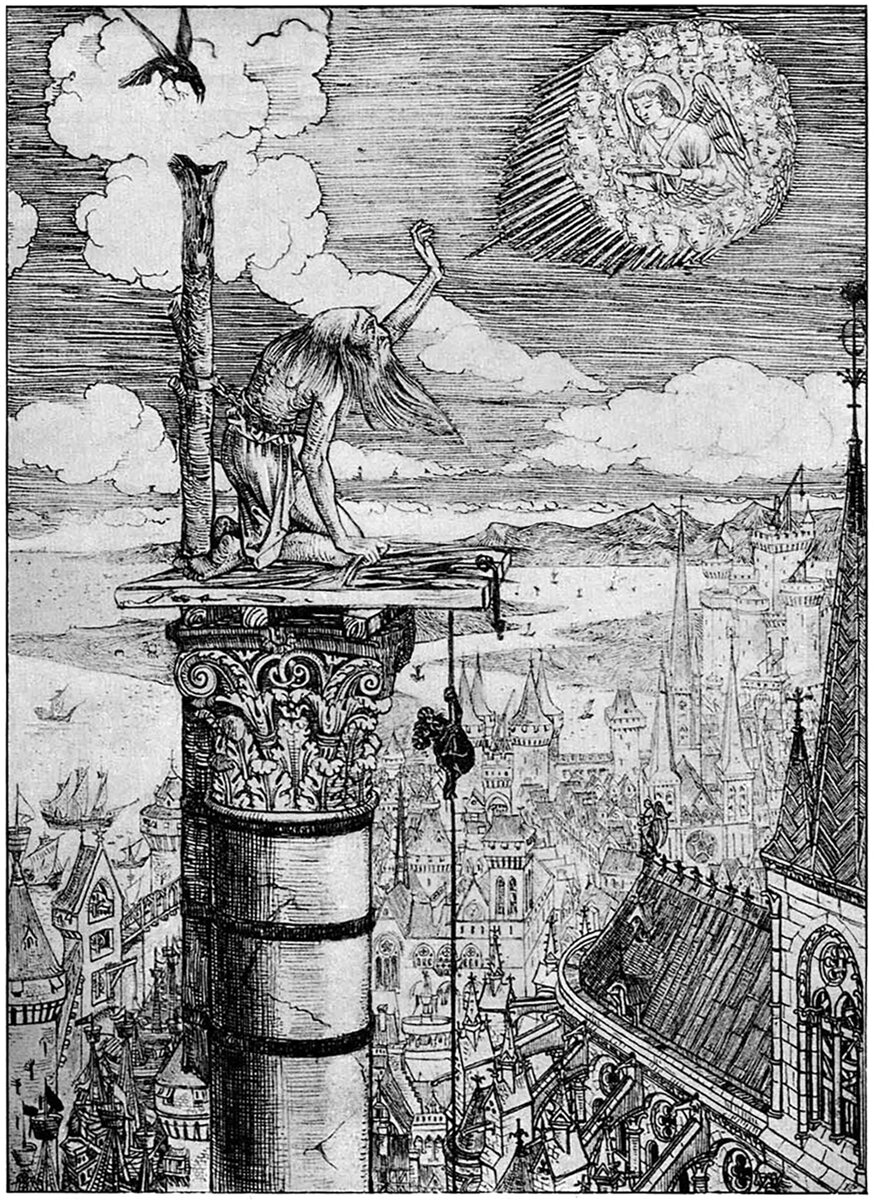

Stylites and the Power of Will

In all my studies on the human need for Verticality, I have yet to come across anything as extreme as the Byzantine stylites. A stylite is a Christian ascetic who chooses to live atop a pillar or column, in an attempt to achieve spiritual salvation. They do this by way of Verticality, by climbing up and away from the surface in order to get closer to the sky, or in this case, God.

Sir George Cayley and the Science of Aviation

Sir George Cayley was an Englishman who is credited as the first person to understand the underlying principles of flight. He was born in Yorkshire, England in 1773, and from a young age he was fascinated with the idea of flight. Cayley was an engineer by trade, and his early engineering career involved many different fields. He shifted his focus to flight around 1850, and his scientific approach to the study of flight has led him to be called the world’s first aeronautical engineer.

The Matrix and Verticality

I was watching the first Matrix movie a few days ago, and the ending scene stuck with me. It features the main character Neo, flying high above the city. Neo is a character that transforms into a God-like figure throughout the movie, and the end scene represents him realizing his full potential. What struck me was the writers’ choice to encapsulate this moment by showing him flying.

"Never regret thy fall, O Icarus of the fearless flight, For the greatest tragedy of them all, Is never to feel the burning light."

-Attributed to Oscar Wilde, Irish poet and playwright, 1854-1900

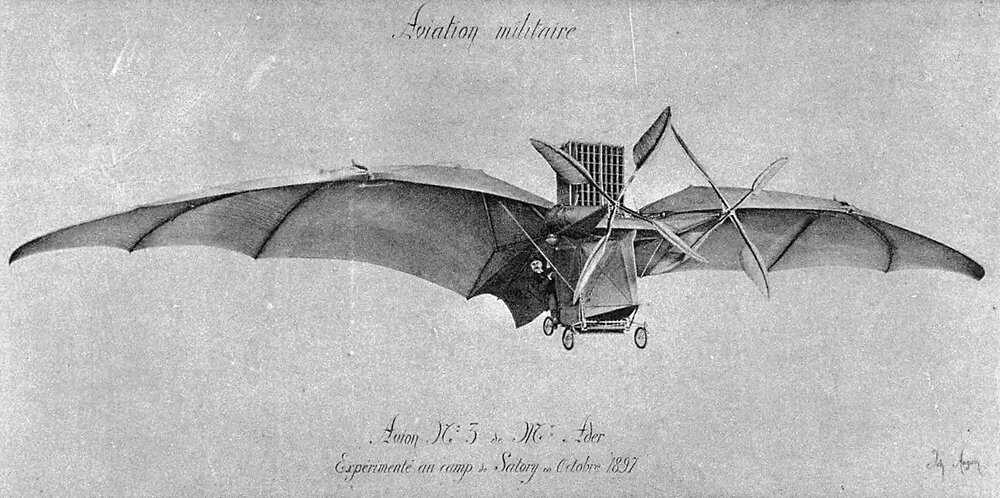

Clément Ader's Éole and Avion III

This is Avion III, an 1897 aircraft designed by Clément Ader. Ader was a French inventor and engineer, who became interested in flight after working on electrical communications and gas ballooning for much of his career. This was the second flying machine he designed. It was an updated and improved version of his first design from 1890, the Ader Éole.

Verticality, Part XII: A Never-ending Struggle

The preceding work has explored our history with Verticality and our struggles to escape the surface of the Earth throughout human history. It began with our context on Earth and our source code that developed in us before we became human in the first place. It then explored our subsequent history up to today and focused on architecture, which is an external manifestation of this inner need to escape the surface. The previous chapter brought us to the present day, which also brings us to the question: will we ever stop pursuing our need for Verticality?

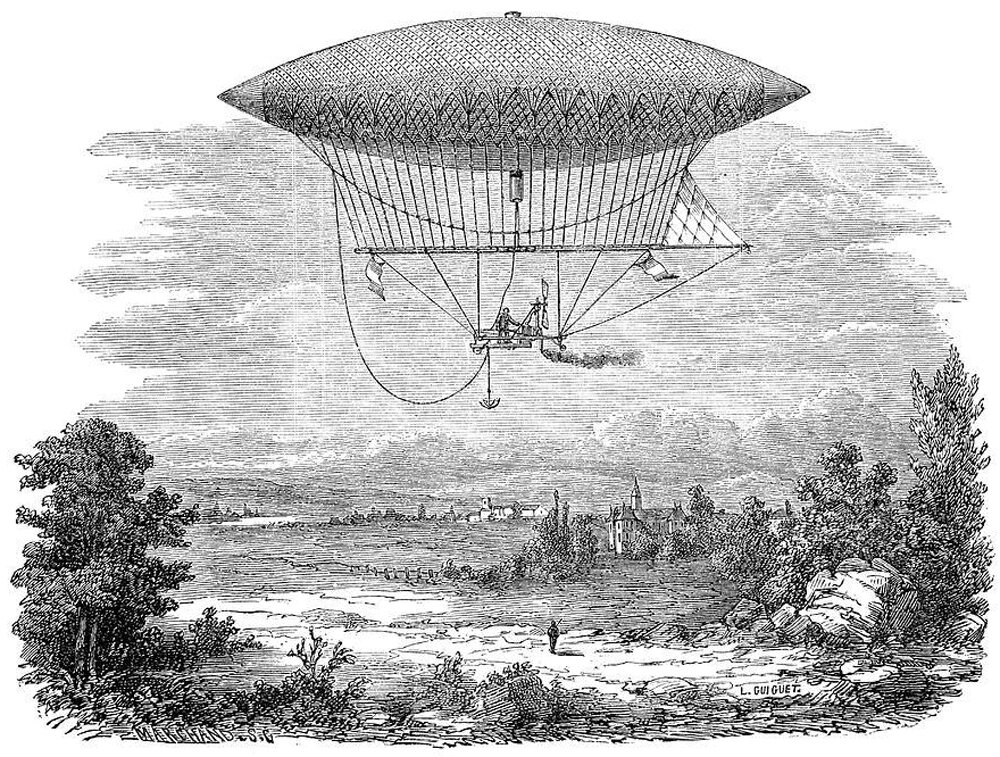

Henri J. Giffard's Airship and Captive Balloon

The airship pictured above was invented by Henri Giffard, which first flew in 1852 from Paris to Élancourt, a journey of 27 km (16.7 miles). I love this image because of the single, solitary figure in the foreground, staring up at the massive airship floating in the sky above. There’s something inspiring about the scale of the two human figures shown, one on the ground looking up, and the other controlling the airship as it floats by, looking down on the landscape below. I see Henri Giffard’s work as an attempt to bring these two worlds closer together.

"For some years I have been afflicted with the belief that flight is possible to man. My disease has increased in severity and I feel that it will cost me an increased amount of money if not my life."

-Wilbur Wright, inventor and aviation pioneer, 1867-1912

Otto Lilienthal, The 'Flying Man'

I have yet to come across a history of flight that doesn’t include Otto Lilienthal. Known as the ‘Flying Man’, Lilienthal was a pioneer of aviation best known for his experiments with gliders and human flight. He made thousands of successful test flights throughout his career, and there are myriad photographs of him before and during these test flights. Pictured above is one such photo of him getting ready to make the leap off a hilltop.

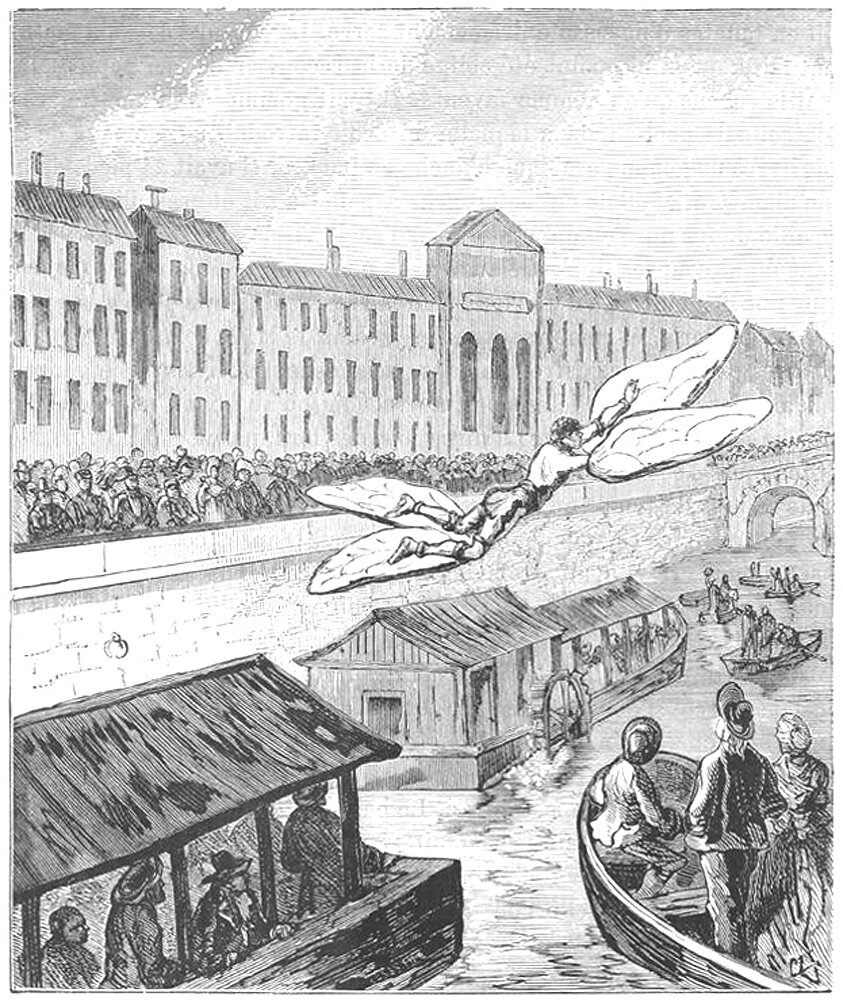

Marques de Bacqueville's Leap of Faith

Pictured above is Marquis de Bacqueville, an eccentric French nobleman best known for his attempt at human flight in 1742. His full name was Jean-François Boyvin de Bonnetot, and he was born in Rouen in 1688. Details about his attempted flight are varied, but apparently on March 19, 1742 in Paris, de Bacqueville announced his intention to fly from one side of the river Seines to the other.

Alexandre Goupil's Sesquiplane

Alexandre Goupil was a French engineer, best known for designing and testing a flying machine in 1883. The machine was a sesquiplane, which is a plane with two sets of wings, one much smaller than the other. It was to be powered by a steam engine housed in a bulbous, streamlined body, which powered a single propeller at the front of the craft. The machine had a wingspan of 6 meters (20 feet), and had space for an operator to stand below the body.