Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

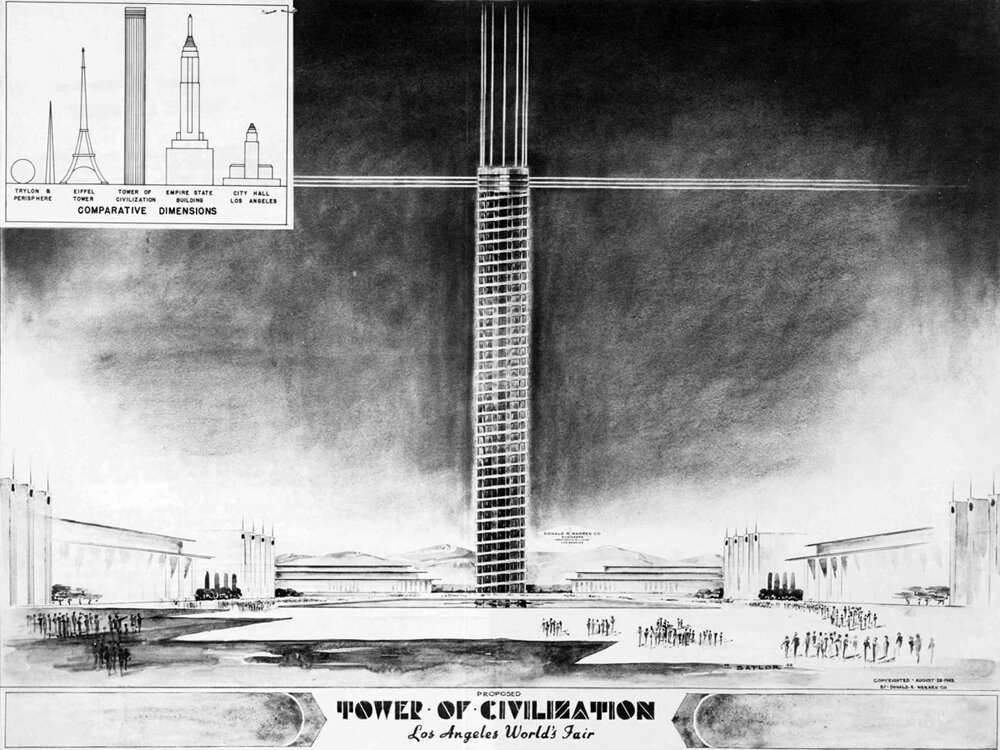

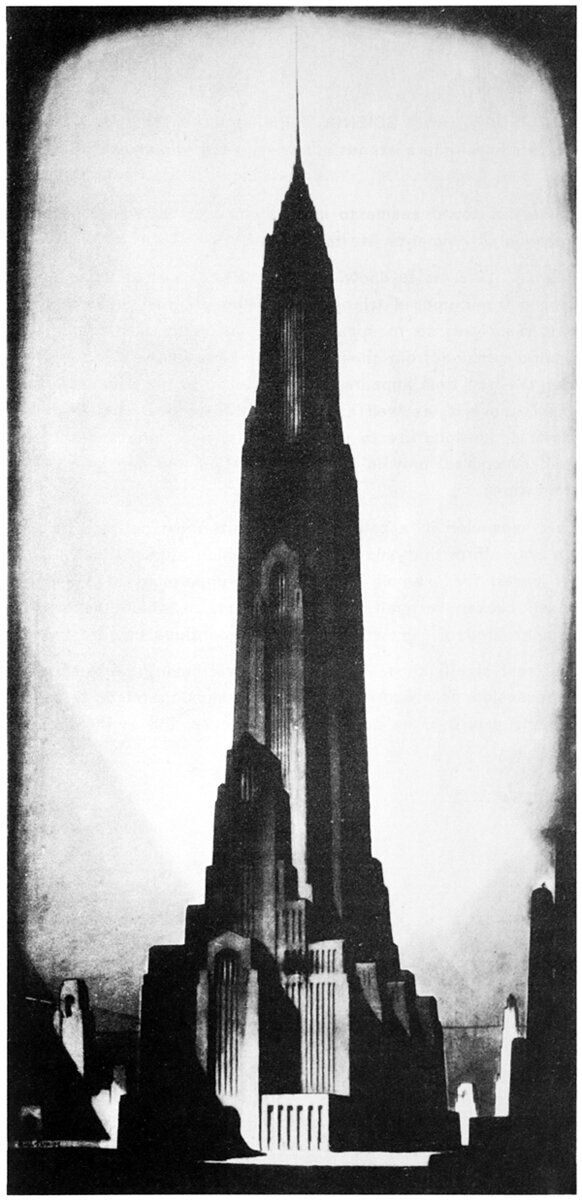

The Tower of Civilization

This is the proposed Tower of Civilization, designed by civil engineer Donald R. Warren for the planned, but never held, 1939 World’s Fair in Los Angeles. It would’ve been the centerpiece of the event and the tallest building in the world, coming in at 393 meters, or 1,290 feet tall. The tower was no doubt meant to signify the status of Los Angeles as a world-class city, and it used Verticality to do so.

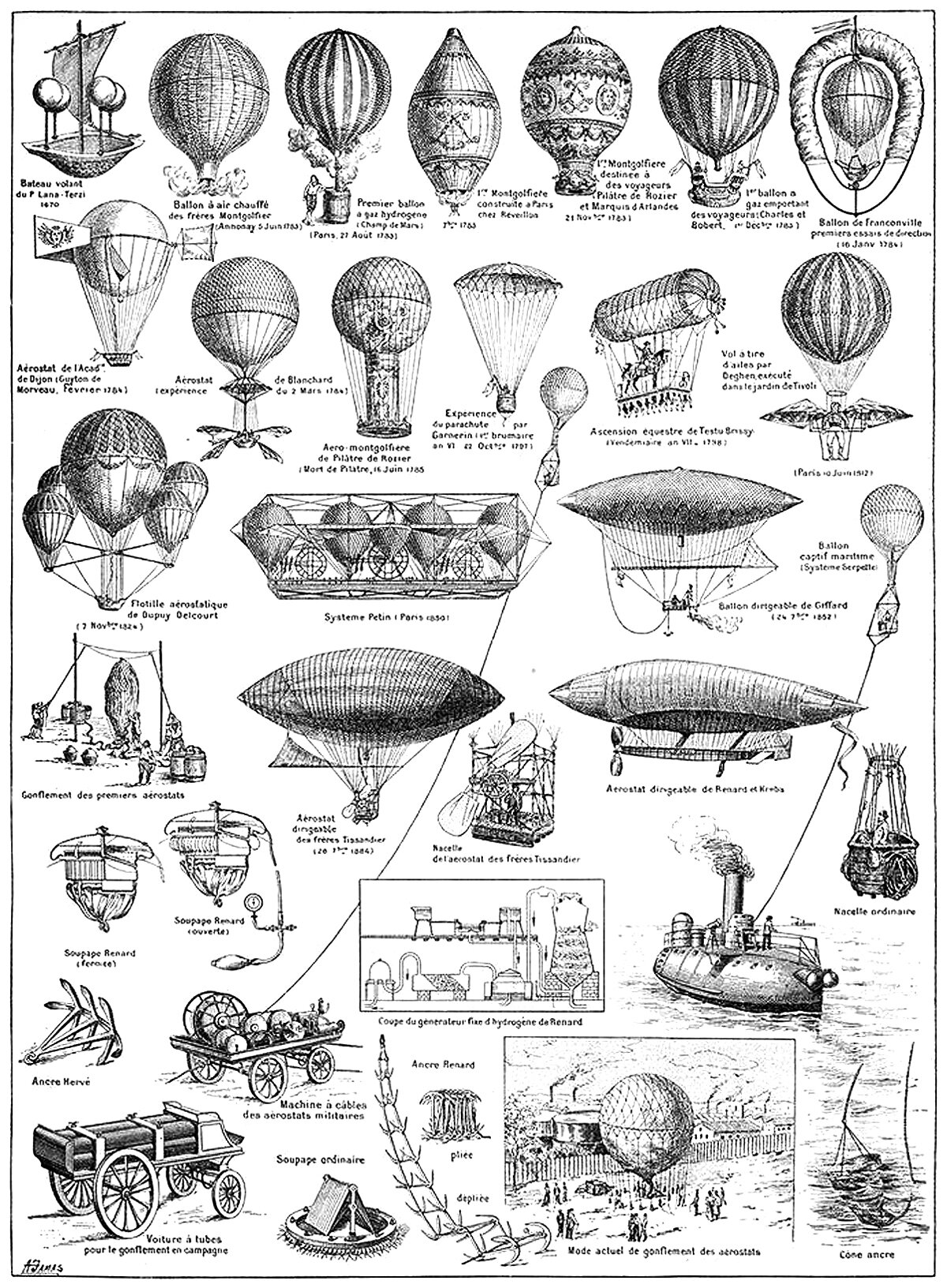

Early Balloon Designs

There are two main strategies when designing a flying machine. The first is a heavier-than-air machine, which relies on creating a lifting force to overcome gravity. The second is a lighter-than-air machine, which relies on a balloon filled with gas or heated air. The above illustration shows famous examples of the latter.

John Damian de Falcuis, the False Friar of Tongland

Pictured above is John Damian, an Italian alchemist best known for an attempt at human flight in 1507. At the time, Damian had been employed by King James IV as an alchemist, and his job was to create gold from more common materials. After he failed to do so and word got around that he was a fraud, he declared he would fly to France with a pair of wings he invented in an attempt to prove his critics wrong,

“I’m learning to fly, but I ain’t got wings. Coming down is the hardest thing.”

-Tom Petty, American singer and songwriter, 1950-2017

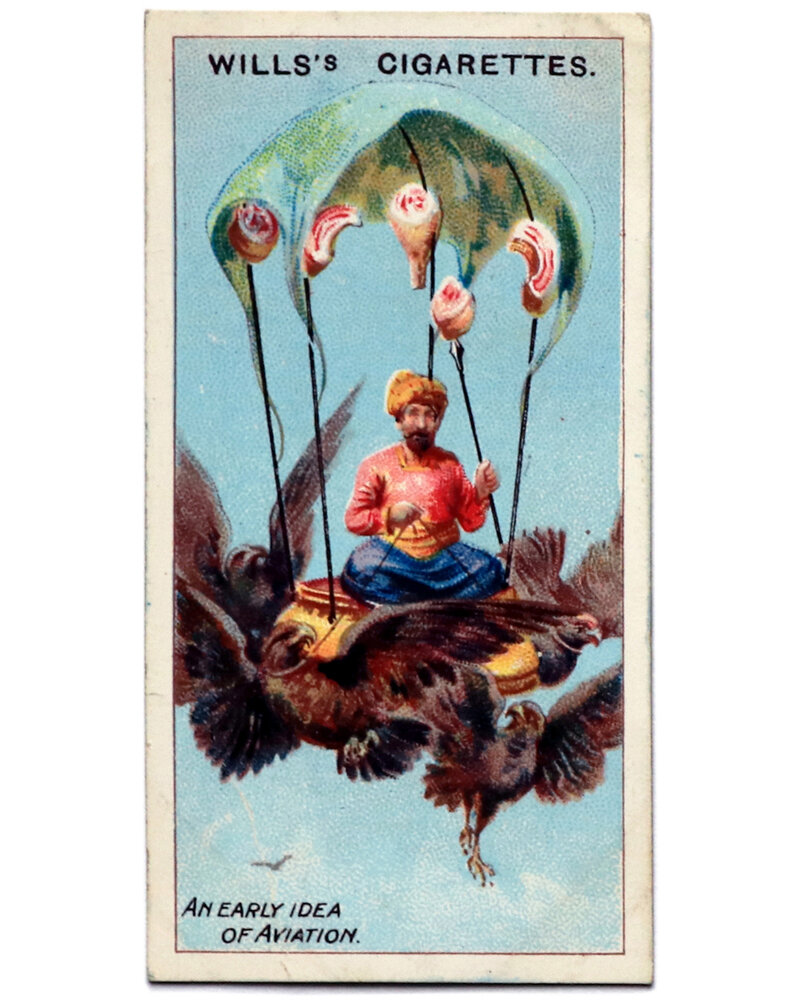

The Flying Throne of Kay Kāvus

The oldest examples of flying machines were the stuff of legends and fairy tales, and the most intriguing ones have endured over time. Pictured above is an illustration of one such tale, showing Kay Kāvus, a mythological Iranian King, and his flying throne. Kāvus was a character from the epic poem Shāhnāmeh, or Book of Kings, which was written circa 975-1010AD by the Persian poet Abul-Qâsem Ferdowsi.

The Unbuilt Inmaculado Corazón de María

I came across the above image recently, and it really caught my eye. It’s a 1910 proposal for a school and church in Buenos Aires, called the Inmaculado Corazón de María (The Immaculate Heart of Mary), and it was designed by Catalan architects Josep Puig i Cadafalch and Josep Goday i Casals. Details are sparse, but the design seems to be a competition proposal that wasn’t chosen. It’s too bad, because it would’ve been an amazing building if it was completed.

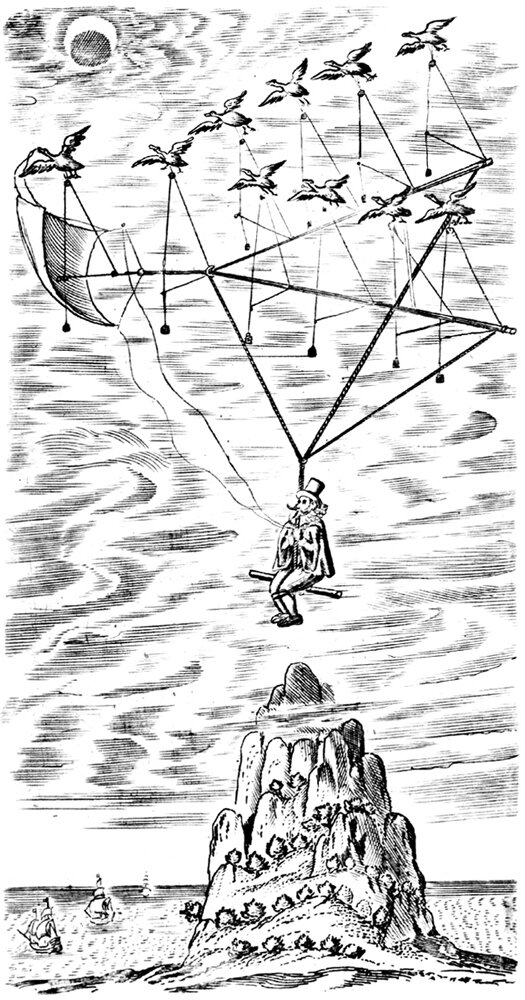

The Man in the Moone

Pictured here is the frontispiece to Francis Godwin’s 1657 book The Man in the Moone. The story is an adventure tale about Domingo Gonsales, a Spaniard who builds a flying machine while stranded on an island. The machine is powered by a flock of large swans, held together by a wooden skeleton with a simple seat at the base for Domingo to sit. From this simple perch, Domingo flies to the Moon and back, among other travels throughout the story.

“You don’t build [the world’s tallest] skyscraper to house people, or to give tourists a view, or even, necessarily, to make a profit. You do it to make sure the world knows who you are.”

-Paul Goldberger, American architecture critic, born 1950.

The Two Cherubs

For nearly all of human history, the space above our heads represented the unknown. Our ancestors would look up in awe, longing to satiate the innate need within us for Verticality. The two little cherubs pictured above encapsulate this innate need to escape the Earth’s surface, and their resulting fame apart from the painting they inhabit serves to illustrate this.

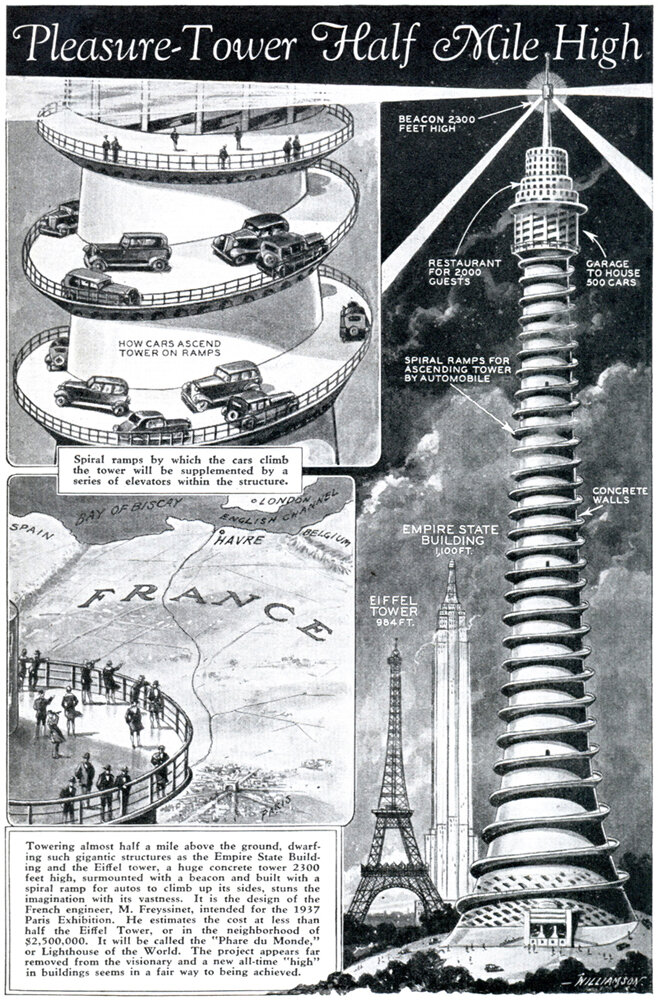

The Phare du Monde Pleasure Tower

Pictured above is a tower proposal from 1933 for the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris. It features an external spiral ramp leading to a parking garage 1640 feet (500 meters) from ground level.[2] Once at the top, visitors would find a restaurant, hotel and observation deck, and the spire contained a lighthouse beacon and a meteorological cabin. The view? Sublime. The design? Utterly ridiculous, unless taken as a satirical statement on civilization’s reliance on the automobile.

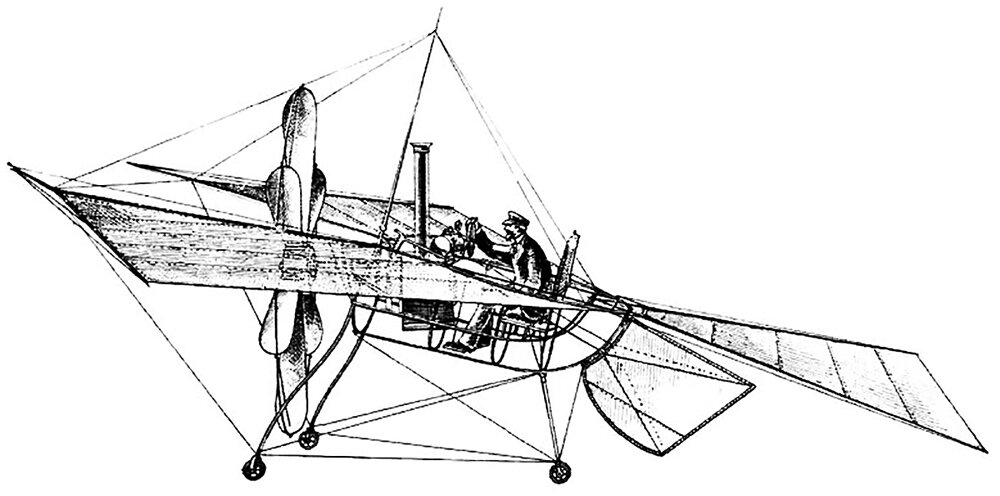

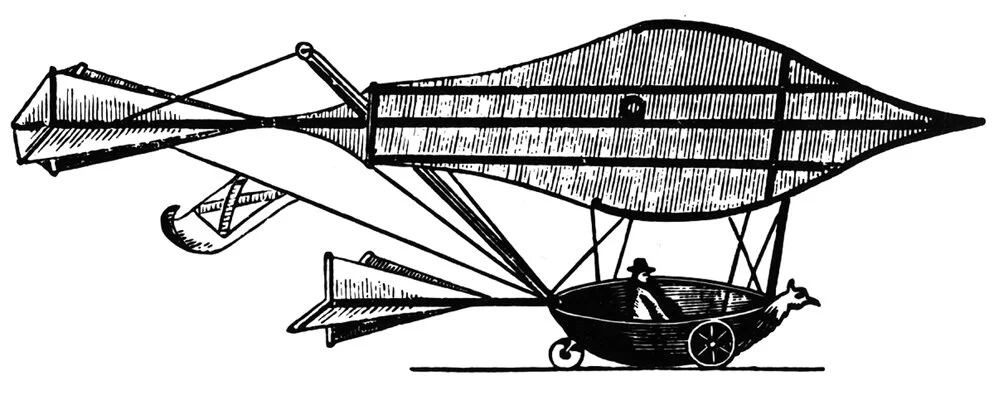

Félix du Temple’s Monoplane

Pictured above is an illustration of Félix du Temple’s design for a monoplane, which he and his brother Luis built and tested in 1874. One such test saw the machine take off from a ski-jump and glide for a bit before safely landing back on the ground. This flight, though short, gave the craft a claim to the first successful powered flight in history.

"[The skyscraper] must be tall, every inch of it tall. The force and power of altitude must be in it, the glory and pride of exaltation must be in it. It must be every inch a proud and soaring thing"

-Louis Sullivan, American architect, 1856-1924

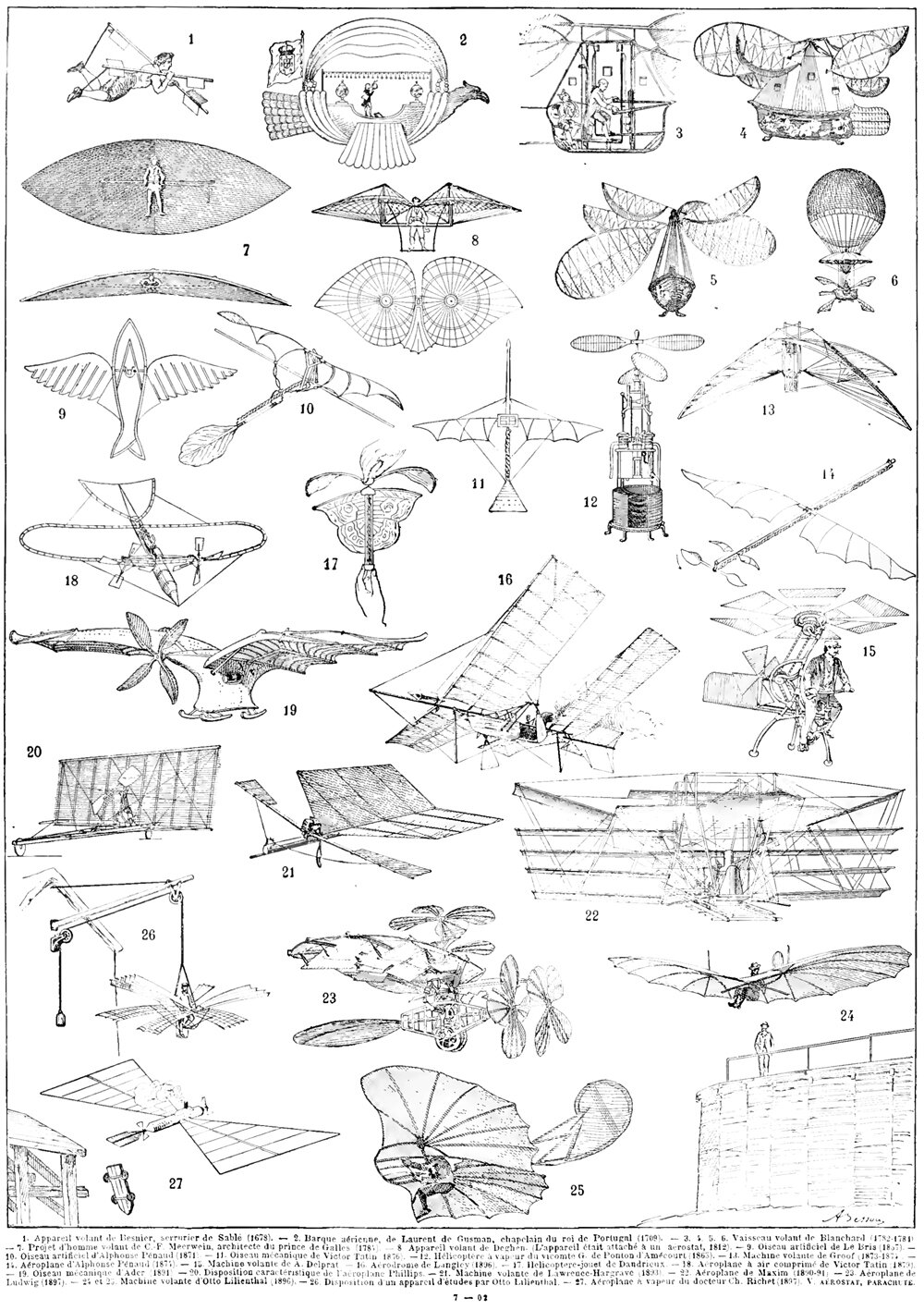

Flying Machines

Throughout history, humans have been fascinated with flight, and some of our more industrious brothers and sisters have dedicated their lives to achieving it. This has led to a rich lineage of ideas for flying machines, and the illustration pictured here shows some famous examples throughout this lineage.

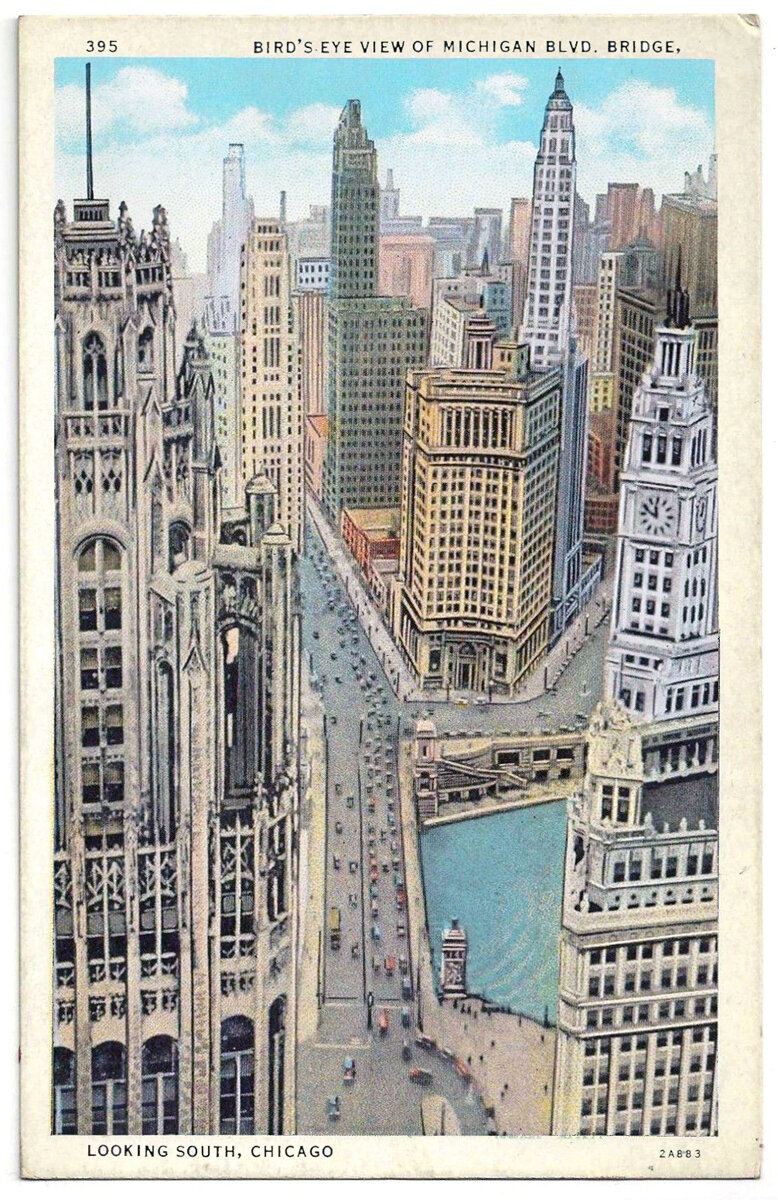

The Urban Canyon

It’s difficult to reconcile the inhuman scale of the skyscraper with the human experience at street level. In most Western cities of today, the experience of walking down the street is largely soul-less, with a relentless street wall rising up on both sides and massive towers rising above that, usually set back from the street wall a bit.

Hugh Ferriss and Religion on the Skyline

Hugh Ferriss was an architect and illustrator, best known for his charcoal renderings of skyscrapers in the first half of the 20th century. Pictured here is an illustration from his 1929 work The Metropolis of Tomorrow, titled Religion. This image and the underlying thought behind it’s creation ties into a larger trend around this time that saw religious structures attempt to re-take the skyline from commerce.

“The problem of the tall office building is one of the most stupendous...opportunities that the Lord of Nature in His beneficence has ever offered to the proud spirit of man.”

-Louis Sullivan, American architect, 1856-1924

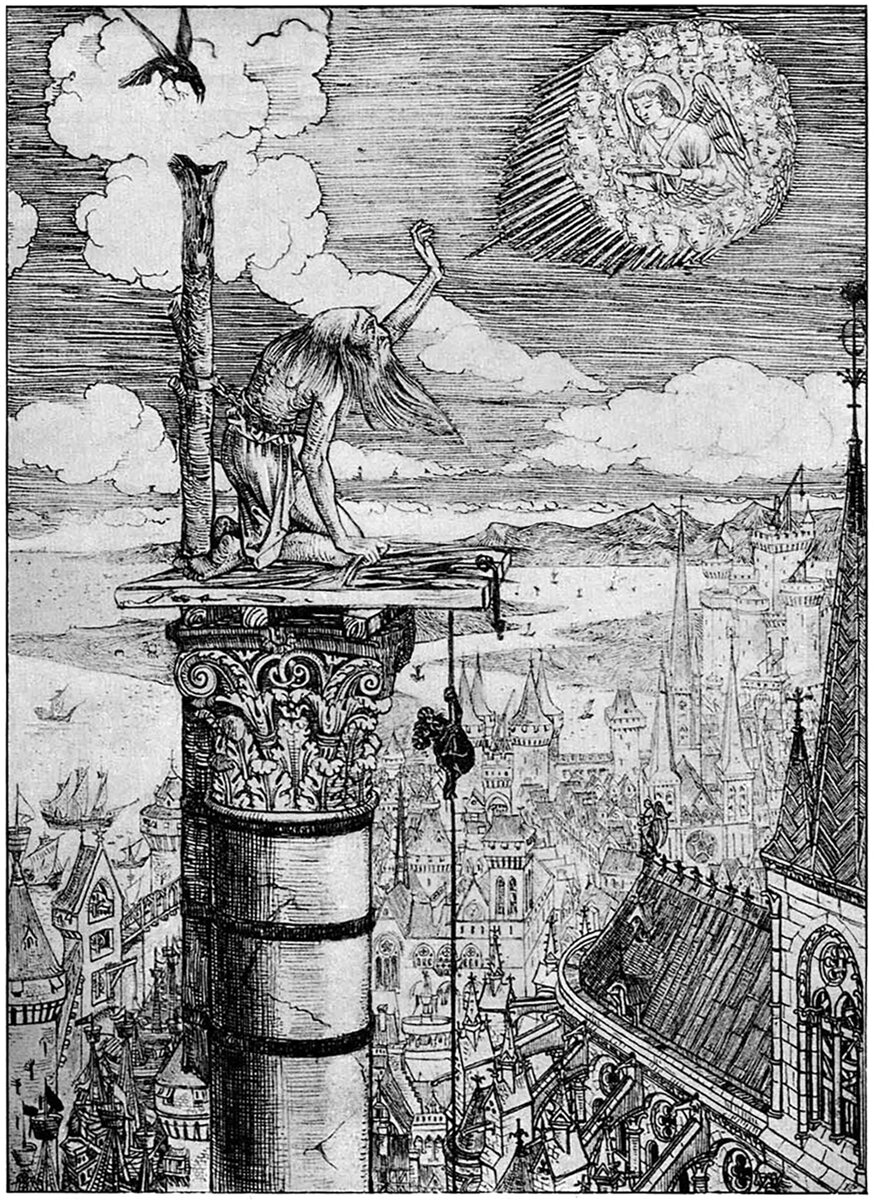

Stylites and the Power of Will

In all my studies on the human need for Verticality, I have yet to come across anything as extreme as the Byzantine stylites. A stylite is a Christian ascetic who chooses to live atop a pillar or column, in an attempt to achieve spiritual salvation. They do this by way of Verticality, by climbing up and away from the surface in order to get closer to the sky, or in this case, God.

Sir George Cayley and the Science of Aviation

Sir George Cayley was an Englishman who is credited as the first person to understand the underlying principles of flight. He was born in Yorkshire, England in 1773, and from a young age he was fascinated with the idea of flight. Cayley was an engineer by trade, and his early engineering career involved many different fields. He shifted his focus to flight around 1850, and his scientific approach to the study of flight has led him to be called the world’s first aeronautical engineer.

The Matrix and Verticality

I was watching the first Matrix movie a few days ago, and the ending scene stuck with me. It features the main character Neo, flying high above the city. Neo is a character that transforms into a God-like figure throughout the movie, and the end scene represents him realizing his full potential. What struck me was the writers’ choice to encapsulate this moment by showing him flying.

"Never regret thy fall, O Icarus of the fearless flight, For the greatest tragedy of them all, Is never to feel the burning light."

-Attributed to Oscar Wilde, Irish poet and playwright, 1854-1900