Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

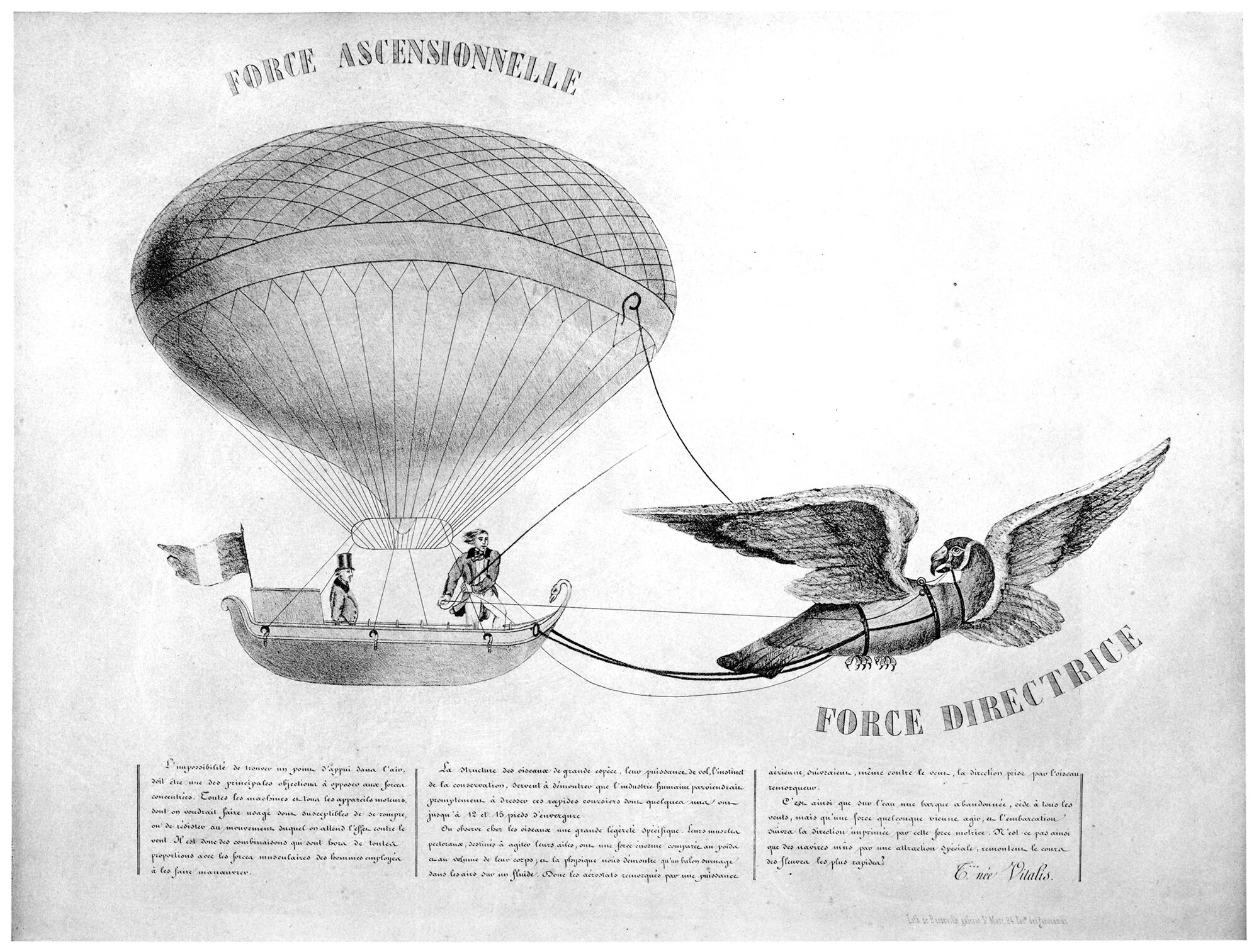

Tessiore’s Balloon Project Towed by a Tame Vulture

Pictured above is a design for a flying machine, consisting of a balloon pulled by a tame vulture. It was originally published in 1845, and was re-published in 1922 in the book L’Aeronautique des origines a 1922. The title of the illustration is Projet de Ballon Remorqué par un Gypaète Spprivoisé, or Project for a Balloon Towed by a Tame Vulture. I’m unable to find any data on the image apart from this, but the content itself is enough to discuss, for obvious reasons.

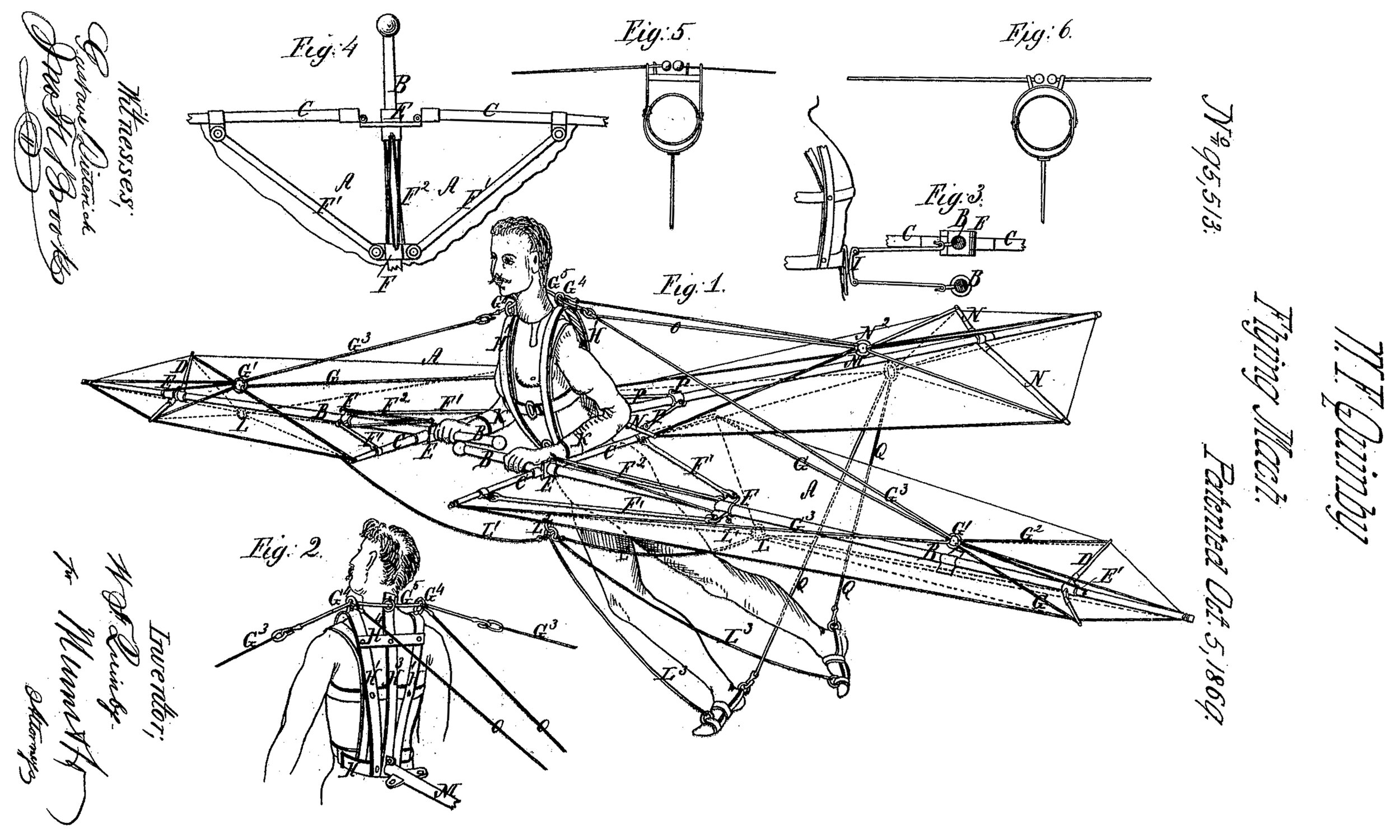

W.F. Quinby and his Three Flying Machine Patents

Pictured above is a patent drawing for a flying machine, designed in 1869 by Watson Fell Quinby, or W.F. for short. It’s the second of three patents for flying machines that Quinby has to his name. It shows a man flying with three wing-like sails attached to him, along with some rudimentary controls at his hands and feet. As with all of Quinby’s designs, we don’t have any photos to compare the patent drawings to, so we’ll have to assume that if he built any prototypes, they weren’t successful.

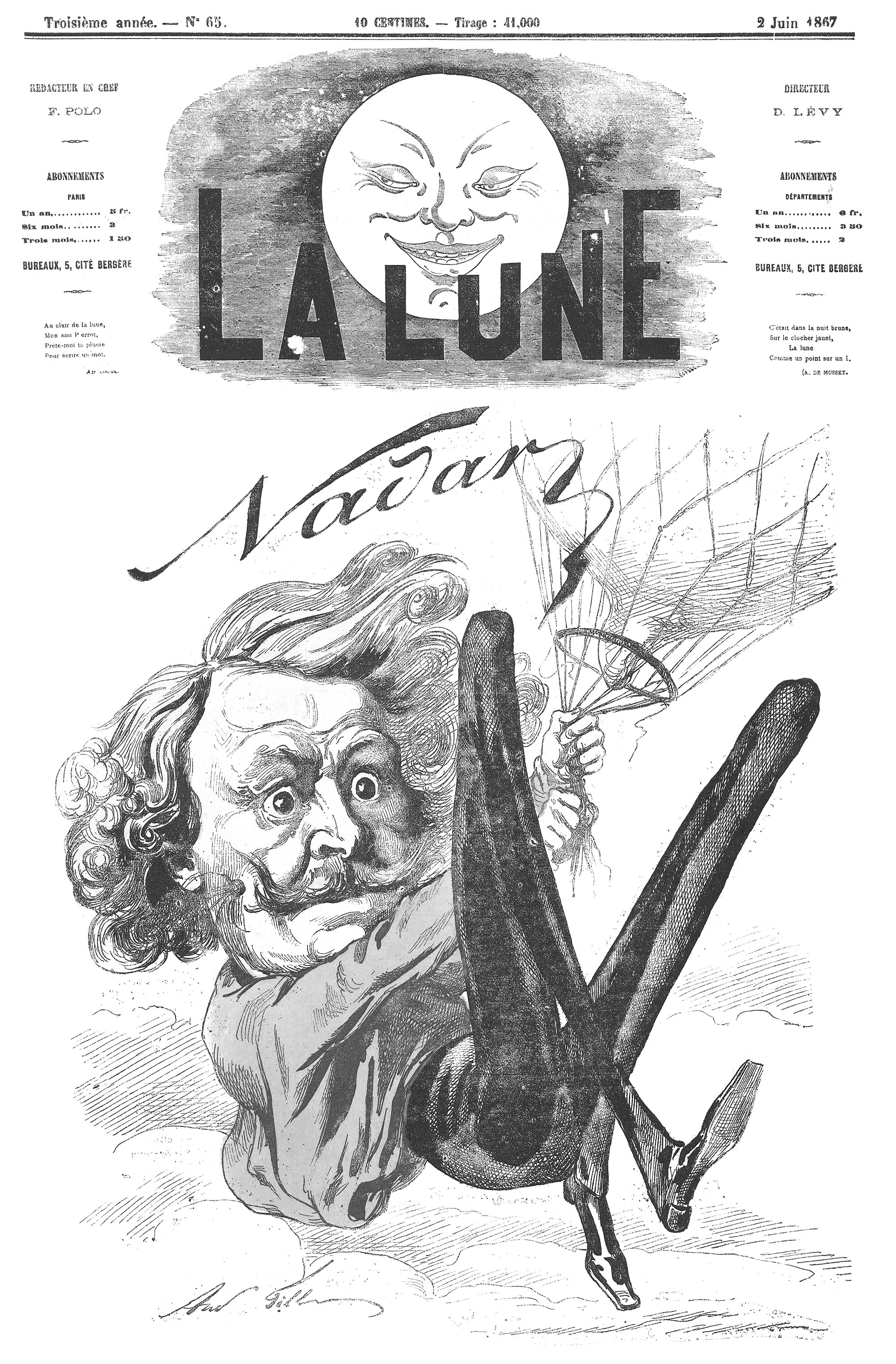

Nadar and the Aerial Perspective

Pictured above is Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, better known by the pseudonym Nadar, who was a French photographer in the nineteenth century, just when aeronautics and air travel were entering popular culture. He was fascinated by human flight, and in 1858 he became the first person to successfully take aerial photographs while he was in a balloon. He subsequently commissioned balloons to be designed and built, and he would allow passengers to take flights with him. He was no doubt obsessed with verticality, and his aerial photographs mark a major turning point in the history of human flight.

“O human race, born to fly upward, wherefore at a little wind dost thou so fall?”

-From The Divine Comedy, by Dante Alighieri, Italian poet and philosopher, 1265-1321.

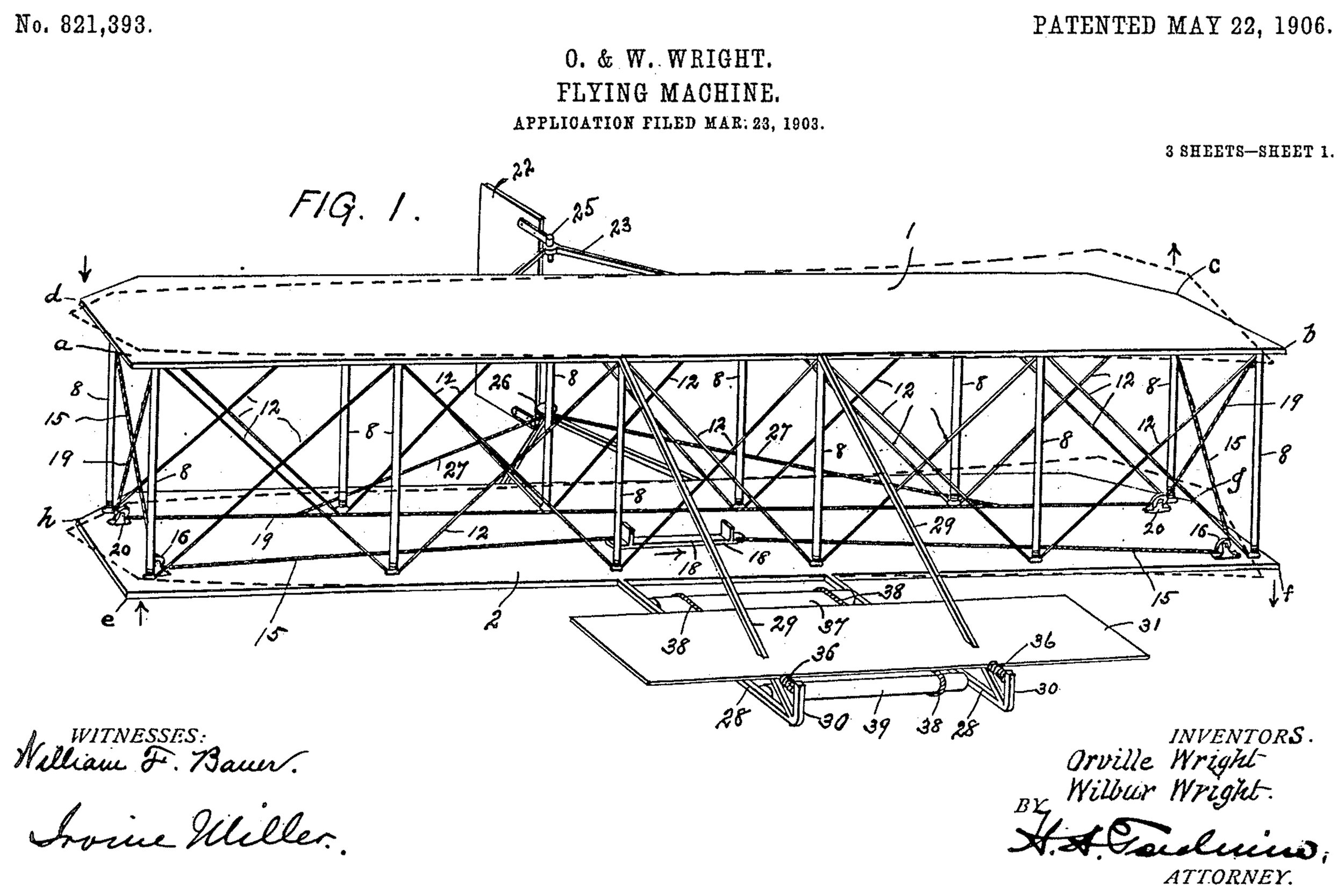

The Wright Brothers’ Flying Machine Patent

I find it fascinating to look at patent drawings of iconic designs throughout history. It’s like you’re getting a glimpse of the design process, before an object enters the public consciousness. Pictured above is a patent for the Wright Brothers’ flying machine, which has since become synonymous with the first ever powered flight. I love how drawings like this strip away any artistic style or vision, and just focus on the object itself. This is a hugely important object that lives on in the history of aviation and human achievement, but it’s rendered here in the most basic, unpretentious way.

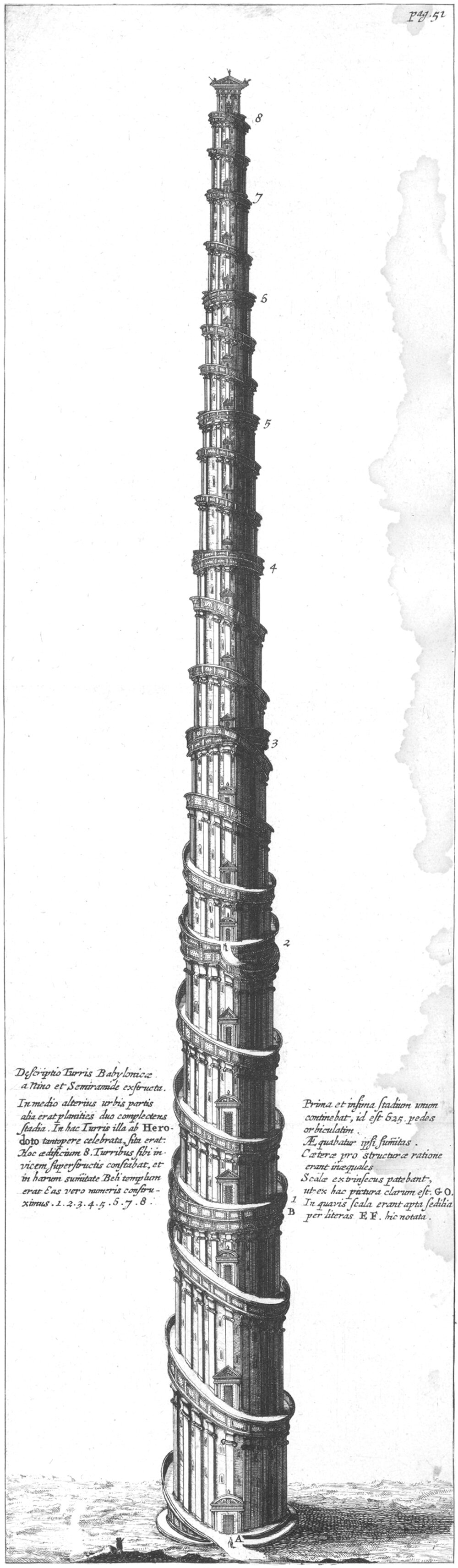

Athanasius Kircher’s Turris Babel

The concept of the Tower of Babel is a timeless one, and throughout history it’s attracted the attention and imagination of myriad individuals. One such individual was Athanasius Kircher, a German scholar and polymath who lived from 1602-1680. His 1679 work Turris Babel explores the concept of building a tower that would reach Heaven, and it was accompanied by a few etchings of such a building.

Flying Carpets and the Power of Flight

Flying carpets are the things of folk tales and fantasy. They are magical objects with the power of flight, and anyone who owns one has considerable power over those who don’t. They can quickly transport their owners across the land at great speeds, and they allow their owners to achieve verticality. Here’s a look at the folk tales that established the myth of the flying carpet.

“The mountains are calling, and I must go.”

-John Muir, Scottish naturalist and mountaineer, 1838-1914

The Isolation of Flight

Have a look at the above illustration. It shows an airship high up in the clouds, isolated and alone up in the sky. This view encapsulates the idea that humans are surface-dwellers, and we’re not built for a life in the clouds. Throughout our history, we’ve spent untold amounts of time and energy trying to escape the surface of the earth, but the reality of such an escape is so foreign to our needs, that it creates a conflict within us.

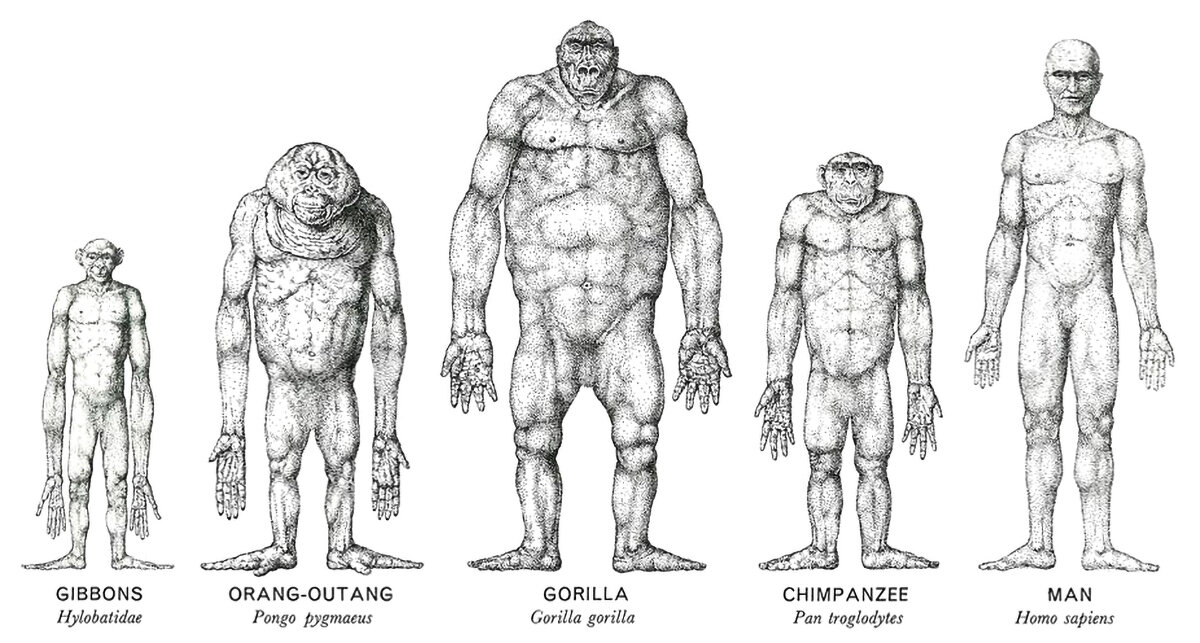

A Comparison of Apes and Man

I’ve been watching a few documentaries on chimpanzees lately, and I’m continuously struck by how similar we humans are to our ape cousins. Our body language and social interactions closely relate, as well as our physical bodies. The major distinction between us and our ape cousins is that we walk upright on two legs. The above illustration caught my eye because It compares the human body to other members of the hominoid family, much like a police lineup. This approach is intriguing, because it shows everyone standing upright on two legs. This, along with removing all hair from the bodies, allows for an easy comparison between the species.

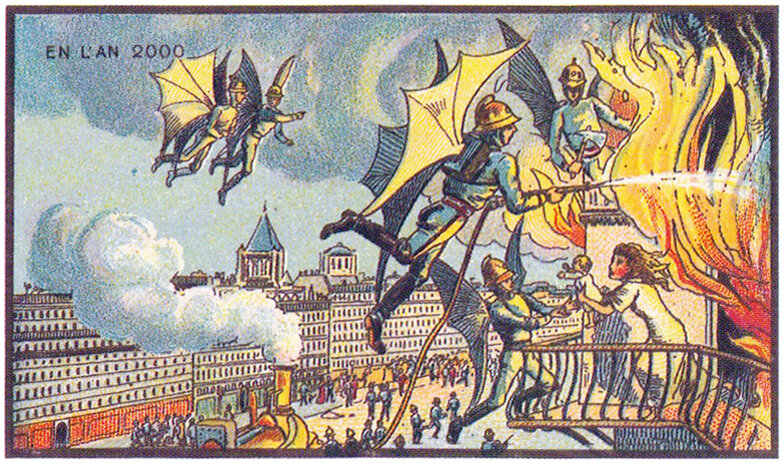

En L’An 2000 : In The Year 2000

Imagine a future where flight is commonplace, and the skies are full of flying people, including police officers, fire fighters, postman, and countless others, zipping around above our heads. That’s what a group of artists led by Jean-Marc Côté dreamed up in 1899 when asked to imagine light-hearted inventions that would contribute to the future. The result was a series of nearly 90 vignettes called En L’An 2000, which means In the Year 2000. The pieces were originally printed as cigarette cards, and later made into postcards. They include a variety of subjects, with a distinct focus on flight and flying machines.

“Towers have always been erected by humankind - it seems to gratify humanity’s ambition somehow and they are beautiful and picturesque.”

-Frank Lloyd Wright, American architect, 1867-1959

Tito Livio Burattini’s Flying Dragon

The above sketch is by Italian engineer Tito Livio Burattini, drawn sometime between 1647 and 1648. At first glance, it’s hard to reconcile a sketch of a flying dragon with a serious proposal for human flight, but Burattini had spent quite a bit of time researching flight, and the sketch was part of a larger treatise on the subject. It was titled Ars Volanti, and throughout the text Burattini wrestled with the idea of flight and how it may be achieved.

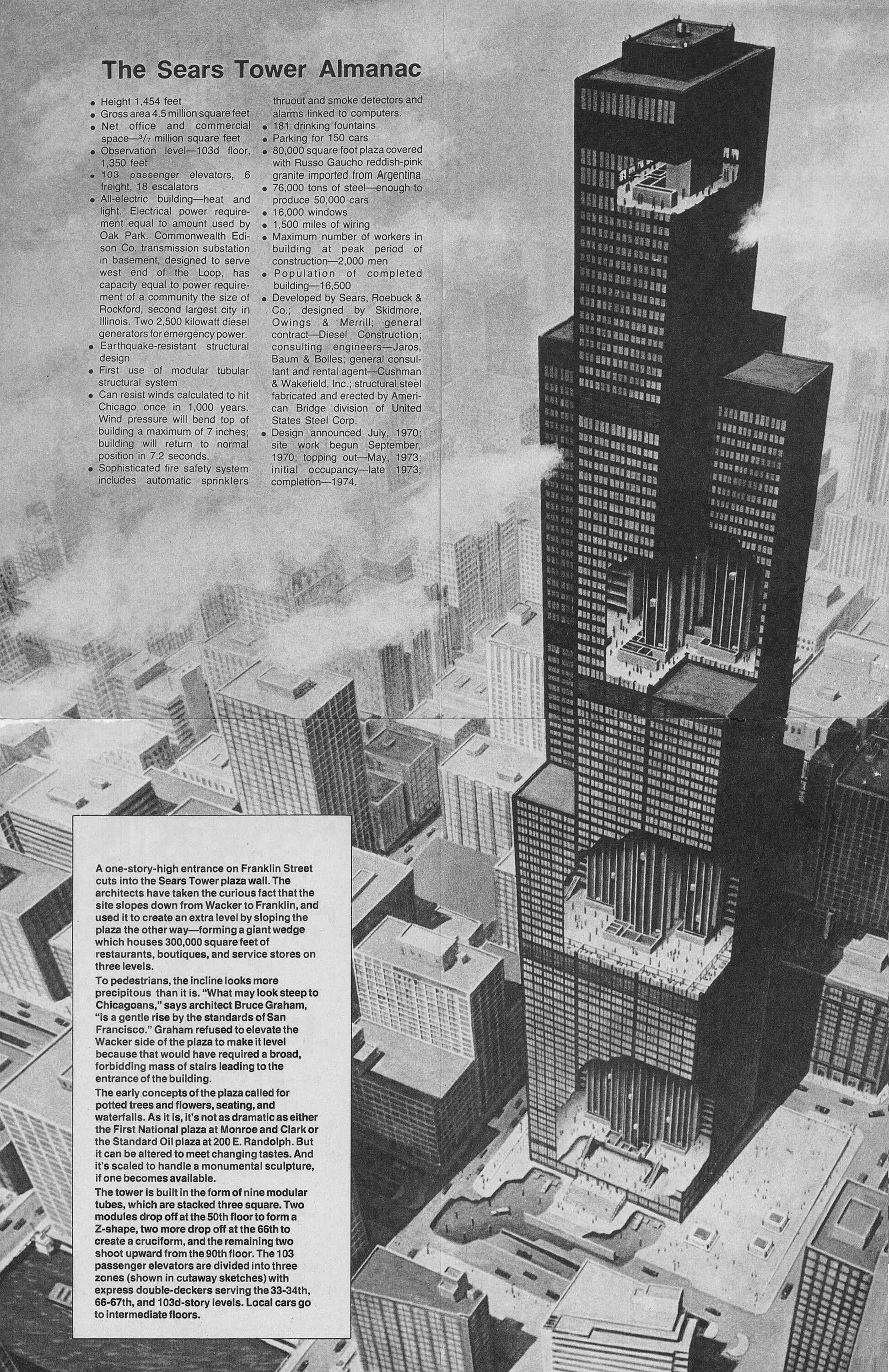

The Original Flat-topped Sears Tower

The above illustration shows the original design for the Sears Tower in Chicago, along with a bunch of factoids related to the scale of the building. Upon first glance, the first thing that stood out to me was the flat roof and lack of the building’s now-iconic antennae. As with most skyscrapers of this size, the building feels quite different without the white spires that are now so closely associated with the skyscraper. Similarly, imagine the Empire State Building without it’s spire, or the John Hancock Center without it’s antennae. It’s just not the same.

The Tower of Babel : A Parable of Verticality

The Tower of Babel is arguably the most storied myth about the human need for Verticality that has survived from antiquity. It’s a legendary tale of a clash between Ego and God, and it acts as a starting point for any worthwhile history of human towers or skyscrapers. Let’s take a look at why it’s been so influential, and why it encapsulates our struggles with Verticality.

“It is impossible that men should be able to fly craftily by their own strength.”

-Giovanni Alfonso Borelli, Italian physiologist and mathematician, 1608-1679.

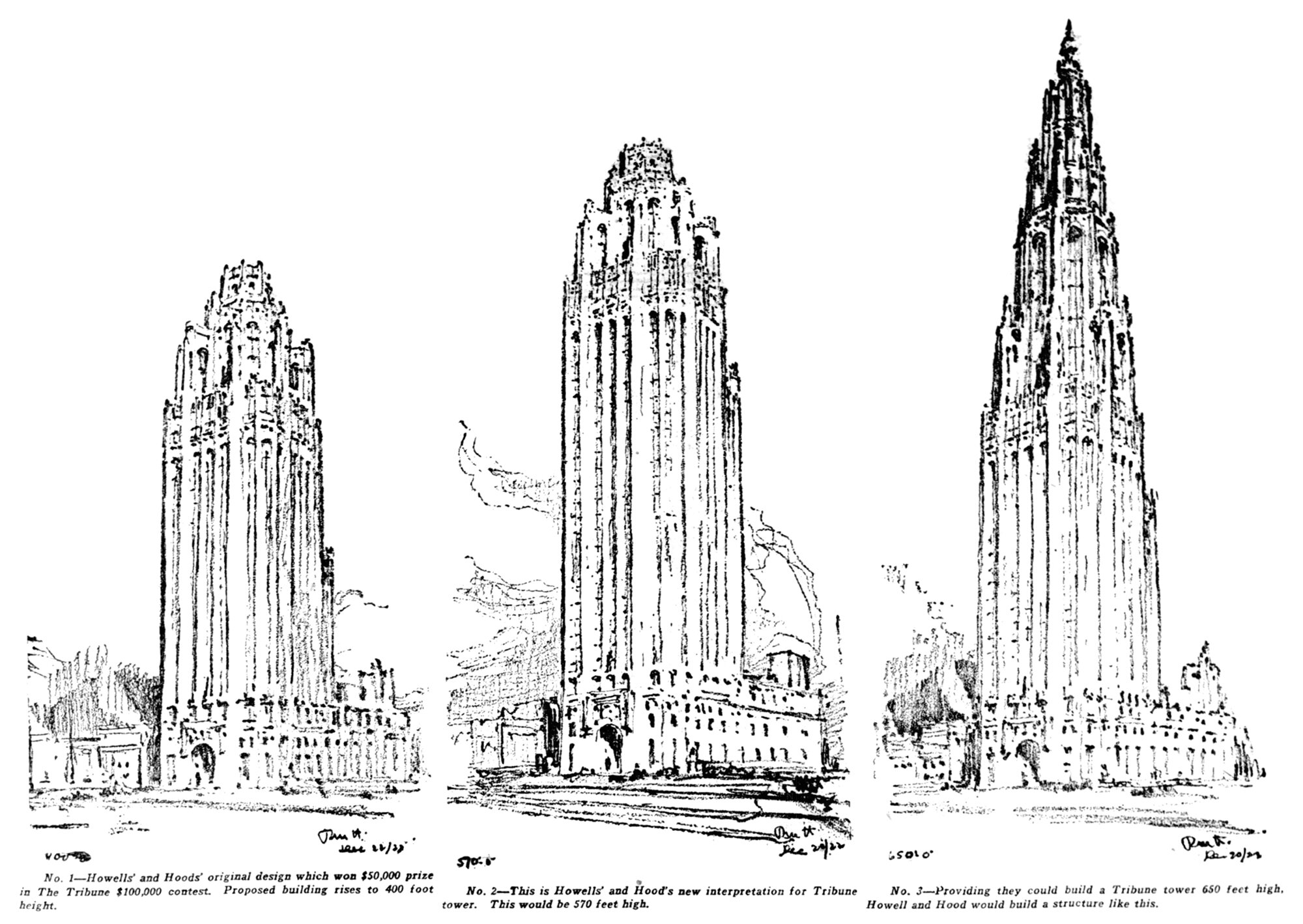

Alternate Realities : Chicago Tribune Tower

Pictured above are three design sketches for the Chicago Tribune Tower. They were drawn after the newspaper asked the architect to study taller options for the building, because they were considering whether or not to build the world’s tallest skyscraper. The increased height would require special approval from the city, so in the end they opted for beauty over height, and didn’t pursue the taller options.

Pierre Ferrand’s Corkscrew Airship

This is Pierre Ferrand de Montfermeil’s 1835 design for an airship, featuring a giant screw mechanism and an elaborate system of fins. Unfortunately details of the design are scarce, and this appears to be the only image we have. According to the authors of the book L’Aéronautique des origines à 1922, it originallt appeared in a brochure titled Projet pour le Direction de l'Aérostat par les Oppositions Utilisées, or Project for the Direction of Airships used by Oppositions.

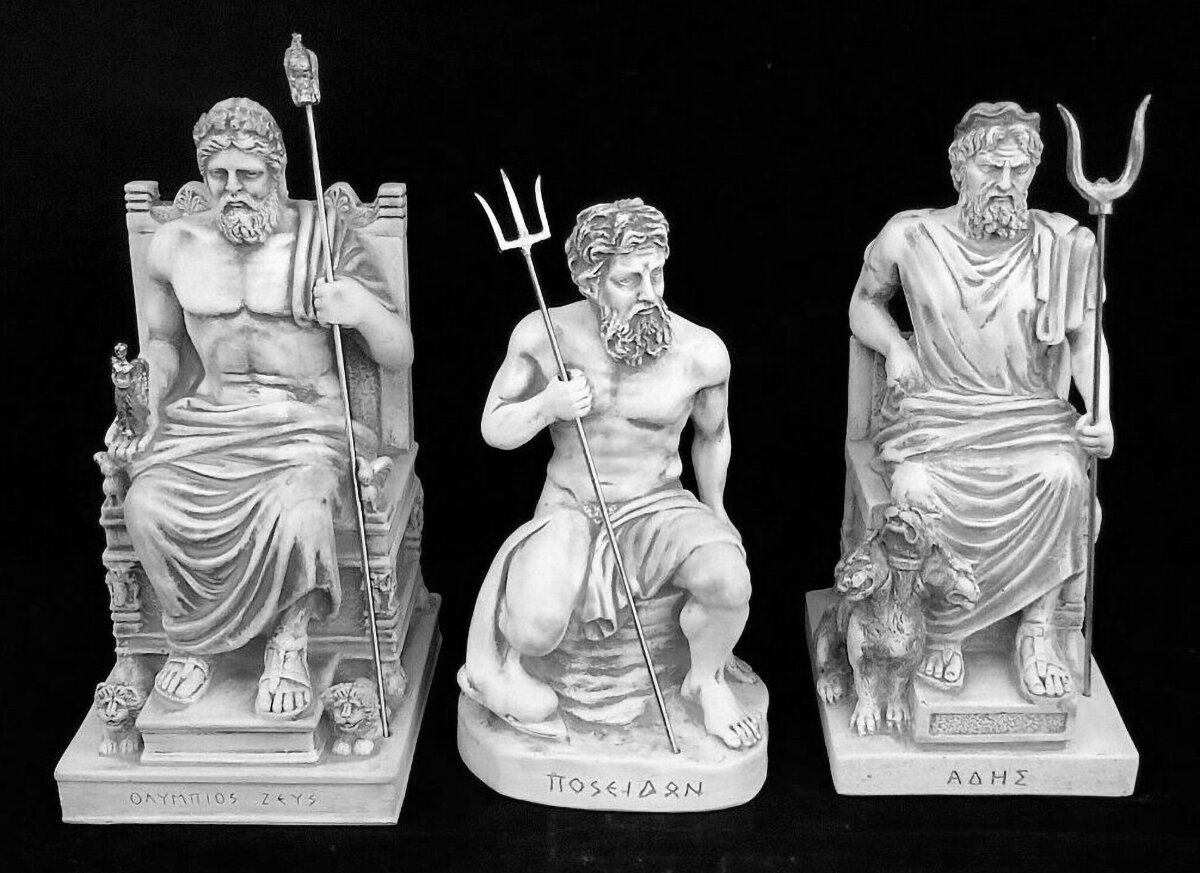

Zeus, Poseidon and Hades : The Verticality of the Greek Gods

Nearly all ancient belief systems are based on the surface, the underground, and the sky in some way. These three concepts represent something primal for humans, and throughout history we’ve attached myriad meanings and stories to the relationship between them. Typically, they’re either represented by an abstract concept or a god. An example of the former is the Christian idea of heaven and hell. An example of the latter is the Ancient Greek gods Zeus and Hades.

“A greater fear I do not think there was ... when I perceived myself on all sides in the air, and saw extinguished the sight of everything but the monster.”

-From The Divine Comedy, by Dante Alighieri, Italian poet and philosopher, 1265-1321.