Charles F. Ritchel's Dirigicycle

The cover of Harper’s Weekly from July 13th, 1878. Pictured is Charles F. Ritchel’s dirigible, or airship. Ritchel’s machine flew a handful of times for private and public demonstrations, and he ended up building and selling a handful of them.

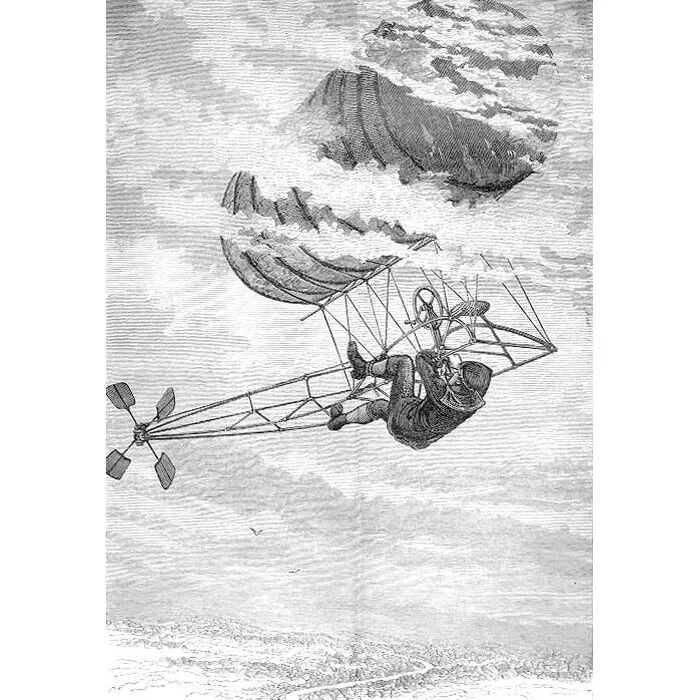

This is the cover of Harper’s Weekly from July 13th, 1878. The issue featured an etching of a man sitting on a tubular frame, suspended in the sky by what looks like an elongated bail of hay. The man pictured is Charles F. Ritchel, and he’s piloting his design for a dirigible. A dirigible is an airship capable of being steered (it comes from the Latin word dirigere, which means ‘to direct’), and the ‘bail of hay’ is in fact a bag of rubberized fabric called gossamer cloth, filled with hydrogen gas. The rigid frame is made of nickel-plated brass tubes suspended from the fabric bag by worsted yarn cords.[1]

Ritchel’s patent drawings for his dirigible. Pictured in detail are the mechanisms that allow the pilot to steer the craft. A hand-crank would spin a propeller, while foot pedals pivoted said propeller in order to steer the craft.

The machine was relatively simple to operate. The pilot would operate a hand-crank with both hands, which would spin a propeller at the front of the frame. In addition, two foot-pedals would pivot the propeller to the left or right. Put these two together, and the pilot had full control over the propeller, which would steer the craft in any direction.[2] This was a major improvement on ballooning technology, since earlier balloon designs were beholden to air currents for movement. This meant that early balloons would take off, catch the wind, and land at a different, unknown location. With Ritchel’s machine, one could take off, guide the craft’s movement while up in the air, and return to the same spot for landing.

Ritchel called his machine the Dirigicycle, and it made a handful of successful test flights in Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts. The first to pilot the machine in public was Mabel Harrington, although aeronaut Mark Quinlan piloted most of the public demonstration flights thereafter. Nearly one month before the Harper’s cover, on June 12, 1878 in Hartford, Connecticut, Quinlan successfully ascended to a height of 200 feet, taking off from a baseball field near the Colt Armory. He then flew over the Armory building and the Connecticut River, before returning to the baseball field for a safe landing.[3] The craft had previously made flights in large, indoor spaces, but the Hartford flight made national news, and it’s credited as the first flight of a human-carrying dirigible in the U.S..

Mark Quinlan making in-flight repairs to Charles Ritchel’s Dirigicycle. He took off from Boston Common in the summer of 1878, and shortly after takeoff the gears jammed, requiring him to make in-air repairs with only a jack knife as a tool. His repairs were successful, and he landed safely, nearly 40 miles from where he took off.

After the success of the Hartford flight, Ritchel and Quinlan traveled to Boston to make subsequent demonstrations to the public. On one such occasion, after taking off from Boston Common, the propeller gears jammed, and Quinlan had to make an in-air repair with only a jack knife as a tool. Pictured above is an illustration of Quinlan making said repair while suspended up in the sky. He successfully repaired the gears and landed safely in Farnumsville, roughly 40 miles outside Boston. The flight took roughly 80 minutes in total.

The public demonstrations of Ritchel’s Dirigicycle were a hit with the public, and often there was a sizable crowd of excited spectators on hand to witness the flights. The inventor had plans to build a fleet of much larger crafts for much longer flights, but it was not meant to be. In the end, he built and sold only a handful of Dirigicycles.

The story of Charles Ritchel and his Dirigicycle encapsulates all the elements of the human need for verticality. Public demonstrations of machines that could fly would attract considerable attention and excitement from the public. Newspapers and magazines would recount the drama, and spectators would watch in awe as their fellow humans would take to the sky and temporarily escape from our surface-bound existence. There was something magnetic about humans achieving flight, and it’s due to our innate need for verticality. The danger of flight and heights is also ever-present, giving these attempts an element of thrills and terror, as experienced by Mark Quinlan after the gears jammed in the skies above Boston. Verticality is something we crave as humans, but the reality of occupying the skies also carries with it considerable danger. It’s a testament to our innate need for verticality that we ignored this danger and took to the skies anyways.

Read more about other ideas for flying machines here.

[1]: Bonner, John, ed. “Flying Machines.” Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, July 13, 1868. 549-550.

[2]: Ritchel, Charles F.. 1878. Improvement in Flying Machines. US Patent 201,200, filed March 2, 1878, and issued March 12, 1878.

[3]: Harper’s Weekly, 550.