James Wines and the Highrise of Homes

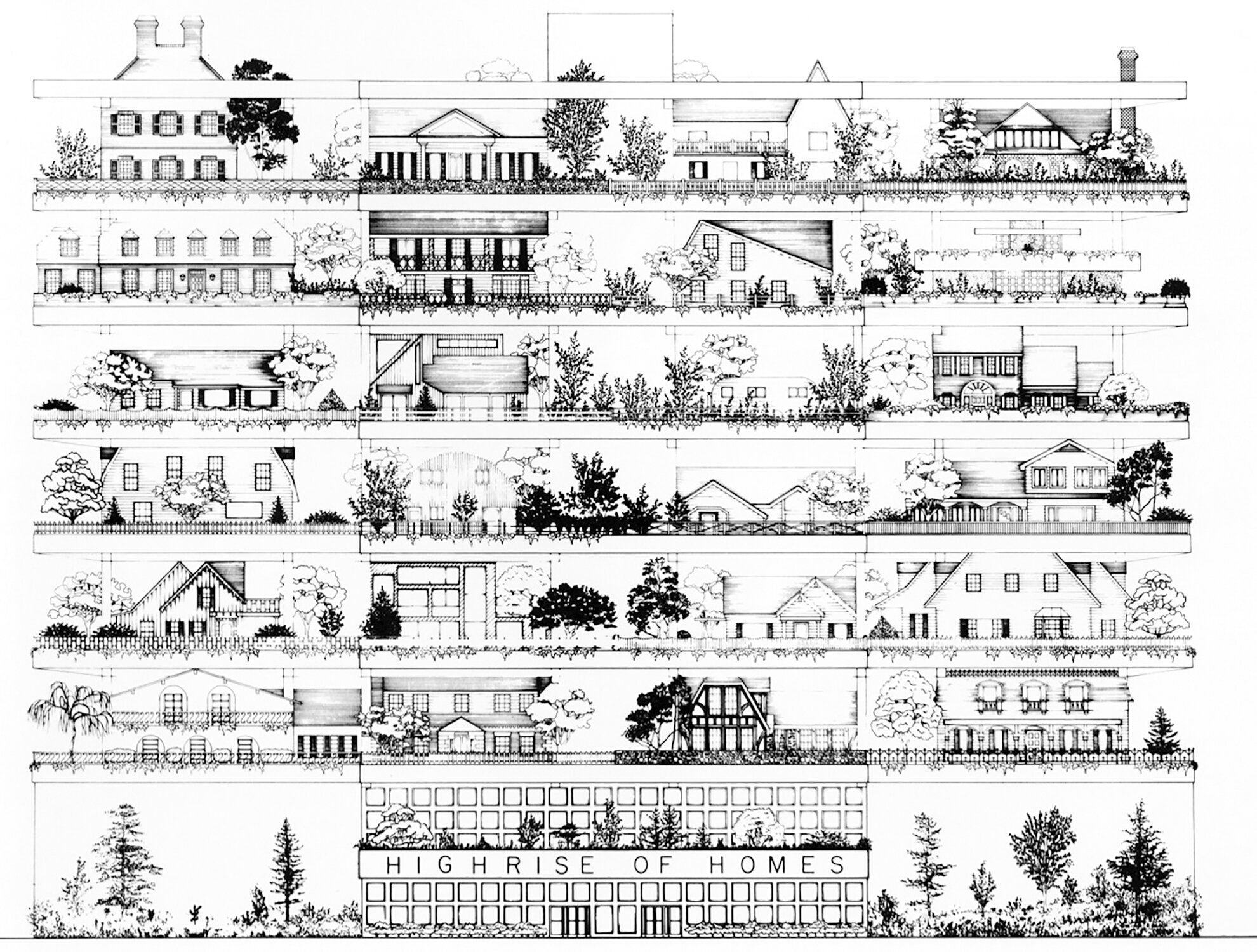

Perspective of the Highrise of Homes by James Wines. Image © James Wines and SITE. Image source.

This is the Highrise of Homes, designed in 1981 by James Wines and his firm SITE. The project consists of a series of stacked levels with individual homes built throughout each level. These homes appear much like the single-family detached homes of suburbia, which results in a curious mashup of typologies. Wines is using verticality to re-arrange a typical suburb into a vertical tower, complete with sidewalks, front and back yards, and pitched roofs. This rearrangement creates some curious scenarios and experiences which are worth pondering.

Axonometric view and plan view of a typical level. Image © James Wines and SITE. Image source.

Wines is attempting to re-create the experience of the surface in the sky, and he’s using verticality to do so. We’re all familiar with what a suburban home is. It’s a single-family domicile that rests upon the surface of the Earth. When one steps out the front or back door, they do so at ground level. These buildings have a direct relationship to the earth beneath them, because they sit directly on top of it. When Wines relocates this typology to the stacked levels of his structure, he fundamentally changes these experiences into something new. He takes suburban elements and applies them to the experiences of a high-rise apartment flat, such that the elements have been ‘suburbanized’. This act alters the original meaning. Front and back yards are now terraces. Handrails and balustrades are now white picket fences. Pitched roofs are now glorified, redundant ceilings. Sidewalks are now open-concept hallways. The building becomes a bespoke mashup of architectural styles and elements that have lost their original meaning. Wines has taken the suburban house and created a decorated shed out of it; the exterior exists to give the impression of something, without actually being that thing.[1]

Elevation view. Image © James Wines and SITE. Image source.

This begs the question: are these desirable homes to live in? One suspects that the height would create value for some part of the housing market. Another intriguing aspect is the ability to construct any type of home on any given ‘plot’. It’s a hyper-customization of an apartment flat, if you will. Also intriguing is the idea of walking out your back door and standing in your backyard, gazing out at the view twelve stories off the ground. It’s a bizarre thought, in its own way, but an interesting one to consider.

View of the courtyard of a U-shaped design. Image © James Wines and SITE. Image source.

[1]: Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown coined the terms Duck and Decorated Shed as two ways that buildings embody iconography. In the Duck example, a building embodies a form, much like a sculpture in the round. In the Decorated Shed example, a building features a false facade that appears to be something ornate and unique, when the structure behind is typical and mundane. In the Highrise of Homes, the ‘homes’ appear as single-family detached homes of suburbia, but the experience is that of a typical apartment flat. It is a false facade.