Verticality, Part X: Conquering The Skies

The race for height that led to humanity colonizing the skies

This chapter is part of a series that compose the main verticality narrative. The full series is located here.

The construction of the Equitable Building in 1915 ushered in a new age of skyscraper design. Humans were now able to escape the surface of the earth with our interior environments, and our need for verticality had ceased to be driven by the unknown. It was now driven by our need to congregate through density and to distinguish ourselves from one-another. Ego had replaced God, and as a result our quest for verticality would become synonymous with human achievement.

Iconography: An obsession with height

The first major example of verticality becoming synonymous with human achievement was the Eiffel Tower in Paris, designed as the entrance to the 1889 World’s Fair. The wrought-iron lattice structure embodies both the mountain and the human body metaphors discussed in the Archetypes chapter. Much like our upright bodies, it is a singular expression of height, and its only function was to assert the dominance of France through its use of verticality. As such, the tower’s height established it as a cultural icon of France, known the world over. The mountain metaphor is also present in its design. It’s form tapers gracefully as it rises, only leaving room for a small viewing platform at its summit. This viewing platform provided humanity with a new perspective on our cities: the bird’s eye view.

Postcard of Eiffel’s 1889 Tower in Paris. The structure was designed for the 1889 World’s Fair. The building’s sole purpose was to display the power of France. It also allowed the public to experience a birds-eye view of Paris.

When ascending a structure of great height like the Eiffel Tower, there is an abstraction that occurs during the ascent. Once at the summit, one gazes down on the city of Paris and experiences a disconnection from the world below. In this position, humans no longer need to gaze upward at the sky; we could now look down upon the earth from above. This bird’s eye view of the world represents our success at finally escaping the surface of the earth. While atop the Eiffel Tower, the surface world is abstracted and we are no longer participants, but observers. Philosopher and author Roland Barthes described this phenomenon as a concrete abstraction of the world, allowing us to see things in their greater structure.[1] One might say we could now see the forest for the trees, and we used verticality to do so.

The Eiffel Tower marked the beginning of an age of iconography in our tall structures. Before its construction, verticality was used to re-create Heaven on earth, before God gave way to Ego. With the Eiffel Tower’s completion, our quest for verticality became about an obsession with height as a means to distinguish ourselves from one-another. This obsession first took hold in New York after the Equitable Building’s aforementioned controversy.

With the passing of the New York City Zoning Laws of 1916, tall buildings were required to set back from their lot line as they grew taller. These setbacks had major effects on building masses and allowed the mountain-metaphor to re-emerge. Just like the Eiffel Tower, as buildings grew taller their form was required to taper, resulting in progressively smaller floors as one ascends. This tapering led to buildings with bulky bases, thin towers and many setbacks or tiers along their height. The resulting forms are generally known as setback-and-tower buildings or the wedding-cake style. Architect and artist Hugh Ferriss compared these buildings to ancient ziggurats, which further reinforces the mountain-metaphor.[2] His studies of possible building masses resulting from the 1916 zoning laws have become icons of early-twentieth century architecture in New York.

Two studies of possible building envelopes that result from the 1916 Zoning Laws in New York City, drawn by Hugh Ferris in 1922. The zoning laws required buildings to set back as they got taller, allowing more light and air to reach street level.

Early examples of these types of skyscrapers used verticality to assert themselves and their locations to the world. The Woolworth Building, completed in 1912 in New York, was built by F.W. Woolworth as a headquarters for his company. The building was the tallest in the world upon completion, and through its name and location, it announced to the world the dominance of Mr. Woolworth and New York, respectively.[3] The building also included an observation deck that was popular among the public. Author Paul Morand wrote about the experience at the observation deck, likening it to being in the open sky, so high up that I feel I ought to be able to see Europe.[4]

A similar approach to verticality can be seen in the height race between the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building. Completed in 1930 and 1931, respectively, these towers embody the setback-and-tower style, and each served to assert the dominance of their builders and the city of New York. With the Chrysler Building, the Chrysler Corporation was announcing itself to the world as a dominant force in the auto industry. The tower also featured an elaborate crown design that has become an icon for the city. It culminates at a needle point, reinforcing the mountain-metaphor with its many setbacks and slender tower form.

Postcards featuring the 1930 Chrysler Building and the 1931 Empire State Building, both in New York. These towers used verticality to assert the dominance of New York, and each has become an icon for the city and for skyscrapers in general.

The Chrysler Building was the tallest building in the world until its rival the Empire State Building was completed in the following year. Due to its height advantage, the Empire State Building has gone on to become much more well-known than the Chrysler Building. Though both are instantly recognizable as icons of New York, the Empire State Building holds a firmer place in popular culture, simply because it’s taller. King Kong chose it for his infamous climb, and it’s been featured in countless establishing shots in movies as an instantly-recognizable symbol of the city. Architecture critic Paul Goldberger described the building as a symbol not only of the New York skyline, but of tall buildings everywhere. He also referred to it as a natural wonder…that would enter the popular lore.[5]

Elsewhere in the world, the need for verticality was being used for political means rather than individual means. In the early 1930s, the Soviet Union planned to build the Palace of the Soviets, which was meant to assert the dominance of the Soviets over the West.[6] The building featured a massive telescoping tower that tapered up to a small platform upon which a statue of Vladimir Lenin was perched. It was political propaganda in built-form, and it used verticality to establish the superiority of totalitarian rule.[7] Though the Palace of the Soviets was never built, a series of shorter towers were constructed in Moscow between 1947 to 1953, dubbed The Seven Sisters. Though not as tall, their purpose was much the same.

Around the same time as the Chrysler and the Empire State Building were competing for height, there was a brief attempt by God to retake the sky from Ego. These buildings used the skyscraper model of verticality to build hybrid structures that included a religious component as part of a skyscraper. Most were never built, save for one prominent example. Constructed in Chicago in 1924, the Chicago Temple Building is an office tower with a chapel perched at its summit. The ‘Sky Chapel’ as it’s called, functions much like the crown of the Chrysler Building. It’s heavily ornamented with a steeple and Gothic flying buttresses, and its goal was to re-establish God among the skyscrapers and skylines of the early twentieth century.[8] Other examples include Convocation Tower, designed in 1921 by Bertram Goodhue for a site adjacent to Madison Square Park in New York, The Broadway Temple, proposed in 1923 for a site in New York, and the 1927 Central Methodist Episcopal Parish Tower, designed by Raymond Hood for a site in Columbus, Ohio. The Convocation Tower and Broadway Temple examples were designed to overtake the Woolworth Building as the tallest building in the world, which confirms the idea that God was indeed trying to upend Ego through the use of verticality.[9] Each of these unbuilt proposals located the temple space near ground level with a high-rise complex built above it. Together, these three buildings are curious examples of verticality being used to establish cultural significance, though this specific attempt would be short-lived, and has yet to re-emerge.

Postcards featuring the 1924 Chicago Temple Building and the proposed 1923 Broadway Temple. These buildings represent an attempt by God to retake the skyline from Ego.

With the age of the skyscraper, humanity began using verticality to derive an identity for ourselves, our cities, and our cultures. One cannot think about Paris or New York without the Eiffel Tower or the Empire State Building coming to mind. Each of these buildings used verticality to represent their locations, and each allowed the public to escape the surface and experience the sky. This bird’s-eye view allowed us to gain a better understanding of our world, but it also isolated us from it. We were no longer of the city, but above it. We had successfully escaped the surface, but we would now take a step further and begin to actively separate ourselves from it.

Abstraction: Building spacecraft

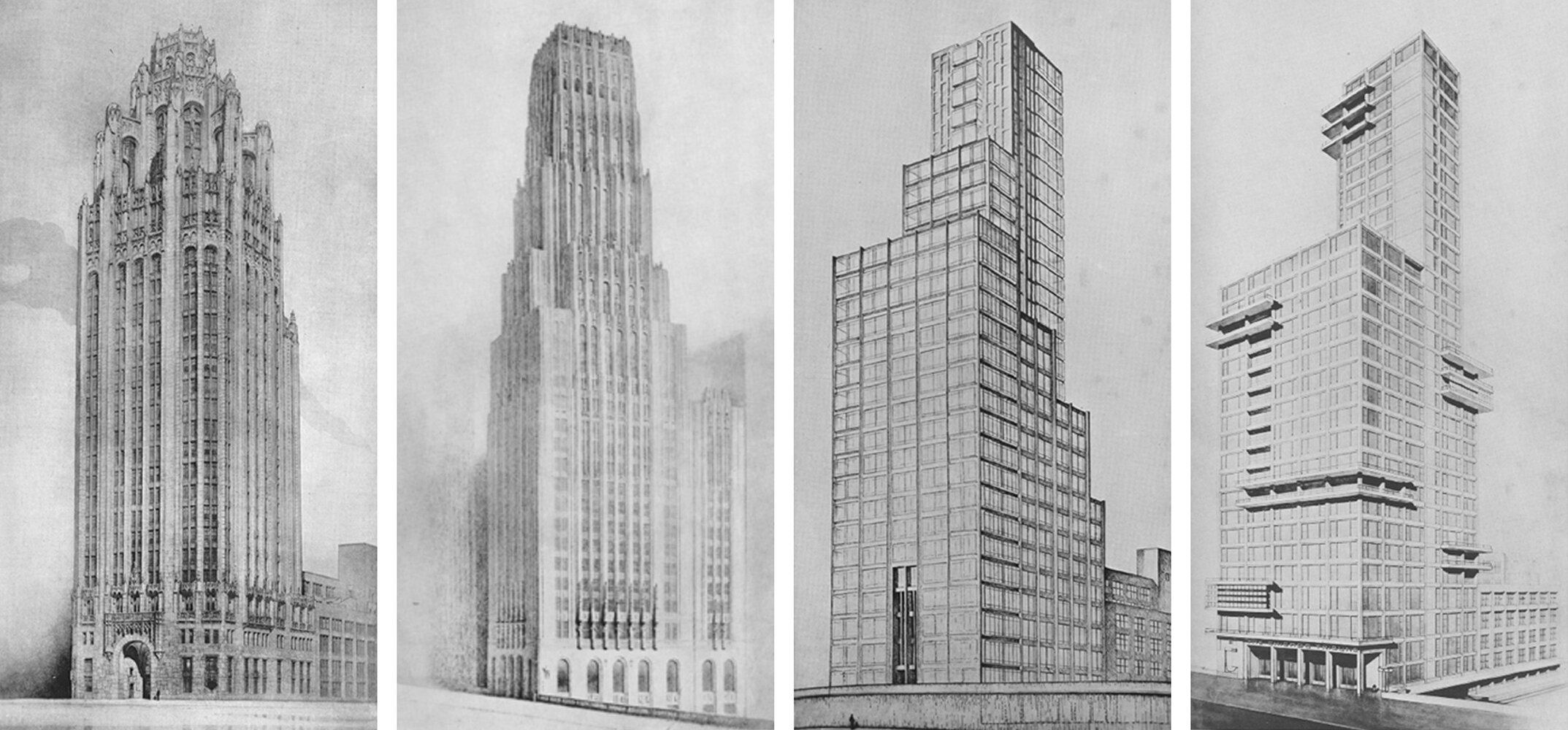

In 1922, the Chicago Tribune held an open competition to design their new headquarters in Chicago. The competition attracted the attention of many world-class architects, and the collection of submissions represents a cross-section of architectural ideologies of the early twentieth century.[10] There were two main value systems at play: modern values and modernistic values. Architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable described these two value systems as a split within architecture, with the former abstract and austere, and the latter ornamental and decorative.[11] A modernistic scheme by Howells & Hood ended up winning, however there were influential designs on both sides that remain unbuilt. Modernistic entries utilized the mountain metaphor and expressive detailing, much like the aforementioned Chrysler Building and Empire State Building. Modern entries are stripped of ornamentation and begin to abstract the form and experience of the skyscraper. This abstraction represents the beginning of a global phenomenon in architecture, commonly called Modernism.

Four designs submitted to the Chicago Tribune Tower competition. The two on the left are modernistic, using the mountain metaphor and expressive detailing, while the two on the right are modern, with austere and abstracted facades. The winning entry by Howells & Hood is on the far left, with Eliel Saarinen, Dwight Wallace and Bertell Grenman’s design next. On the right is Max Taut’s submission, with Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer’s design on the far right.

The emergence of Modernism brought about a revolution in architecture and a shift in our struggles with verticality. This shift ultimately led to the worldwide proliferation of the International Style. We had successfully escaped the surface with our skyscrapers, and the battle between God and Ego was over. We now needed full control over the environment within our newly-created spaces in the sky. This control would require us to isolate ourselves completely from the surrounding world. In short, we needed to build spacecraft. A seminal example of the International Style is the Seagram Building in New York. Built in 1958, Seagram represents a complete disregard for its surroundings, as if it flew in from some distant place and landed in Midtown Manhattan. Its interior is climate-controlled, and as a result the experience is exactly the same regardless of where the building is located. Building systems such as heating, cooling, and lighting were designed to provide a consistent, unchanging environment regardless of the conditions outside. Formally, there is no mountain metaphor or expressive crown here. Every floor is the same size and shape. It is a pure manifestation of the universal human need to escape the surface, and due to this purity Seagram would become an icon for the International Style and its paradigm would be copied the world over.

The Seagram Building, built in 1958. The tower is meant to be a spacecraft, completely indifferent to its surroundings. The box-shaped tower contains a stack of identical floors that provide identical experiences to its users, save for the view. Photo © Ezra Stoller.

Buildings like Seagram can be found in every major city around the world. The abstraction of the interior environment could be replicated anywhere, so the principles could be adopted regardless of location. The most egregious example of this is most likely the Tour Montparnasse in Paris. The building is wildly out of context, as if a black, hulking spacecraft landed within the historical fabric of the city. Much like the Seagram, the building is a tall, undifferentiated stack of floors that provides a completely abstracted experience of Paris. Save for the views, the building could exist anywhere and the interior experience would be exactly the same. Due to these facts, the building has been loathed by Parisians and visitors to the city alike.[12]

Unlike earlier skyscrapers that gave an identity to their owners and locations through verticality, International Style buildings disregarded their surroundings. These spacecraft would be built all over the globe in exactly the same fashion, with similar designs, using similar materials, regardless of their location. Humanity was still attempting to escape the surface through our skyscrapers, but we had lost the human element in the process. Our primal connection to mountains and our own bodies had been forgotten, and we were actively cutting ourselves off from the outside world. The rampancy of Modernism was not without its critics, however, and luckily our buildings would subsequently begin to erode into more humanistic designs in order to create more diversity in the sky.

Keep reading: Verticality, Part XI: Breaking the Box

[1]: Barthes, Roland. The Eiffel Tower and Other Mythologies. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, 1979. 8-9.

[2]: Ferriss, Hugh. The Metropolis of Tomorrow. Mineola: Dover Publications, 2005. 98.

[3]: Goldberger, Paul. The Skyscraper. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1981. 85-86; Twombly, Robert. "The Skyscraper as Icon, 1890-1910." In Power and Style: A Critique of Twentieth-Century Architecture in the United States, 27-38. New York: Hill and Wang, 1995. 27-28.

[4]: Morand, Paul. New York. The Book League of America, 1930. 53-54.

[5]: Goldberger, 85-86

[6]: Binder, Georges. 101 Of The World's Tallest Buildings. Victoria: Images Publishing Group, 2006. 10.

[7]: Ong, Aihwa. "Hyperbuilding: Spectacle, Speculation, and the Hyperspace of Sovereignty." In Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global. Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. 207.

[8]: Wolner, Edward W. "The City-within-a-City and Skyscraper Patronage in the 1920's." Journal of Architectural Education 42, no. 2 (Winter 1989): 17.

[9]: Van Leeuwen, Thomas A.P. The Skyward Trend of Thought: Five Essays on the Metaphysics of the American Skyscraper. 's-Gravenhage: AHA Books, 1986. 75-76.

[10]: Banham, Reyner. Theory and Design in the First Machine Age. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1970. 268-269.

[11]: Huxtable, Ada Louise. The Tall Building Artistically Reconsidered: The Search For A Skyscraper Style. New York, NY: Pantheon Books, 1984. 39-44.

[12]: Glaeser, Edward. "What's So Great About Skyscrapers?" In Triumph of the City: How our greatest invention makes us richer, smarter, greener, healthier, and happier, 135-64. New York: The Penguin Press, 2011. 156.